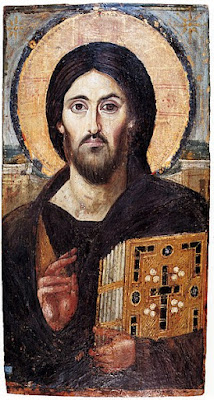

Our Eighth Day Institute 2022 Symposium was a wonderful event, held Friday and Saturday, January 14 and 15 at St. George's Orthodox Cathedral in Wichita, Kansas. Of course there were some glitches--the main one being that Rod Dreher, one of the plenary speakers, could not come to Wichita because he had tested positive for Covid and had lost his voice so he couldn't even participated digitally. All of the speakers spoke to everyone attending because we had no breakout sessions. And the presentations were wonderfully balanced between practical matters of current issues and theological explorations of the true model and how we should imitate Him: Jesus Christ. Thus, the icon for the event:

The Pantocrator from Saint Catherine's Monastery.

Carl R. Trueman, from Grove City College in western Pennsylvania, a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in DC, and author of

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution among other books offered two presentations, analyzing the cultural changes in the way we identify ourselves. Dr. J (Jennifer Roback Morse) of the

Ruth Institute also gave two presentations on the effects of those changes on the family, on fathers and mothers, on children, on schools, etc, etc. While he outlined the situation we face, Dr. J offered tactics, ways of thinking and responding, all at the service of renewing the true doctrine of the family: a man and woman who marry for the sake, not of their appetites and whims, but for the loving stability of a home for children, who know who their parents are, know their identities, and live with both parents, unless a tragedy occurs.

Then Father Alexis Torrance and the Reverend Hans Boersma offered some theological and spiritual foundations--above and beyond the practical steps we have to take to help our culture to return to the reality of humanity, the family, and the common good--upon which to base our efforts. Boersma outlined how Hugh of St. Victor offered his monks a model of lectio divina based on spiritual analogies within the structures of Noah's Ark:

Sex and the Imagination: Focusing the Mind: Delusions of the self—and the sexual problems linked to them—do not just happen. They are caused by a wandering imagination. This talk discusses how the 12th-century spiritual master Hugh of Saint Victor tried to anchor his students’ character: through a mural painting of Noah’s Ark. We will turn to Noah’s Ark in our own 21st-century pursuit of focus and stability.

Here's another

version of his presentation.

2. Perpetual progress or eternal rest? Contemplating the eschaton in St Maximus the Confessor

3. Perfection before our eyes: St Theodore the Studite on the humanity of Christ

4. I am called by two names, human and divine: dogma and deification in St Symeon the New Theologian

5. The energy of deification and the person of Jesus Christ in St Gregory Palamas

We were disappointed that Rod Dreher could not come and that he was ill. Nonetheless, I though it was a very successful gathering--in part, just because we gathered--in which we confronted issues Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians face in our families, workplaces, churches, and friendships and were reminded and consoled by the victory of Jesus Christ over sin and death through His Incarnation and Paschal Sacrifice.

I think the Symposium, of all the events we present at Eighth Day Institute, is the most accessible and important. Ad Fontes--the summer theological week--purposefully emphasizes the differences between and among Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians (our different views of Baptism, Salvation and sin (this summer's topic) and is the more scholarly gathering. The Inklings Festival is a family Oktoberfest event, celebrating Tolkien, Lewis, Chesterton, Sayers, et al. It's fun and literary at the same time, which as an English major I appreciate.

The Symposium, though, gives us all a chance to gather and think about our lives as Christians, the challenges we face inside and out, and thus offers renewal so we may do as St. Peter the Apostle advises:

But even if you do suffer for doing what is right, you are blessed. Do not fear what they fear, and do not be intimidated, but in your hearts sanctify Christ as Lord. Always be ready to make your defence to anyone who demands from you an account of the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and reverence. Keep your conscience clear, so that, when you are maligned, those who abuse you for your good conduct in Christ may be put to shame. (1 Peter 3:14-16)

I certainly hope that anyone reading this could come to an Eighth Day Symposium some day: perhaps next January?!?