Blessed Philip Powell (sometimes spelled Philip Powel) (2 February 1594 – 30 June 1646) was a lawyer who became a Benedictine monk and priest, serving as a missionary in England during the period of recusancy. He was martyred at Tyburn. Powell is usually said to have been born in Tralon, Brecknockshire, Wales. From his youth he was a student of law, taught principally by David Baker, (who would later become a Benedictine himself, taking the name Augustine Baker). At the age of sixteen he went to study at one of the Inns of Court, London, and afterwards practiced civil law.

Three or four years later he received the Benedictine habit, becoming part of the community of St. Gregory at Douai (now at Downside Abbey, near Bath). In 1618 he was ordained priest and in 1622 left Douai to go on mission in England. In around 1624 he became chaplain to the Poyntz family at Leighland, Somerset.

When the English Civil War broke out he retired to Yarnscombe and Parkham in Devon. He then served for six months as chaplain to the Catholic soldiers in General Goring's army in Cornwall, and, when that force was disbanded, took ship for South Wales. The vessel was captured on 22 February 1646, and Powell was recognised and denounced as a priest.

On 11 May he was sent to London and confined in St. Catherine's Gaol, Southwark, where his treatment brought on a severe attack of pleurisy. His trial, which had been fixed for 30 May, did not take place till 9 June, at Westminster Hall. He was found guilty of being a priest and was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn. It is recorded that that when informed of his death sentence, Powell exclaimed "Oh what am I that God thus honours me and will have me to die for his sake?" and called for a glass of sack (or sherry). He was beatified by Pope Pius XI in 1929. He is one of the six Gregorian martyrs: Blessed George Gervase (1608) ; Saint John Roberts (1610); Blessed Maurus Scott (1612); Saint Ambrose Barlow (1641); Blessed Philip Powell (1646), and Blessed Thomas Pickering (1679) honored at Downside Abbey.

Further research and information on the English Reformation, English Catholic martyrs, and related topics by the author of SUPREMACY AND SURVIVAL: HOW CATHOLICS ENDURED THE ENGLISH REFORMATION

Saturday, June 30, 2012

Friday, June 29, 2012

Some Relevant Current Events

1)--This story from the BBC:

A collection of centuries-old skeletons excavated in Oxfordshire and stored in a museum are to be reburied as part of a "celebration" mass.

The human remains were found during the extension of a church graveyard in Eynsham, leading to excavations between 1989 and 1992.

Father Martin Flatman, of St Peter's Catholic Church, said he was pleased he could give them a "proper burial".

Six bodies are thought to be monks from the medieval Eynsham Abbey.

The remains of two women and a man have been dated to after the Reformation, and are believed to have been secretly buried in the consecrated ground.

The Catholic church was built on the site of the ancient abbey in the 1940s.

'Rib fractures'

Father Flatman said: "Suddenly it dawned on me that I didn't know where the bodies were. I found out they were in the museum's storage and I applied to have them back.

"As a Catholic we honour the dead and we wouldn't want to leave them, particularly those faithful 16th and 17th Century Catholics who faced persecution."

The finding of those bodies at Eynsham Abbey is another demonstration of what Eamon Duffy indicated in his article in The Telegraph I posted yesterday: for too long, England has ignored its past. In burying those recusant faithful, Father Flatman is reminding England of a time when a Catholic was forced to conform to the national church at birth, at her marriage, and at death.

2)--This interview from Hilary Mantel in The Telegraph:

Mantel was raised a Roman Catholic and educated at convent school.

However, the 59-year-old writer said child abuse scandals involving Roman Catholic priests demonstrated the “cruelty” and “hypocrisy” of the church.

Asked if she would call for a priest on her deathbed, Mantel replied: “No. I might very well call for a Church of England vicar, but I would not call for a Catholic priest.

“I’m one of nature’s Protestants. I should never have been brought up as a Catholic. I think that nowadays the Catholic Church is not an institution for respectable people.”

Which reminds me of the Oscar Wilde comment, "The Catholic Church is for saints and sinners alone. For respectable people, the Anglican Church will do." (Remember that Oscar Wilde became a Catholic on his deathbed.) Francis Phillips responded here in The Catholic Herald. Mantel may think she was being remarkably current and astute ("nowadays") in her comment, but she is ignoring the past five hundred years in England, too--not to mention the Gospel stories of Jesus dining with tax collectors and publicans--they weren't respectable either. For a literate and learned person, she made a most illiterate and ignorant statement.

3)--This story from Maryland:

The Rev. Edward Meeks and his flock attended to a "million and one details" last week in the run-up to a momentous day for their church. People to talk to. Flowers to arrange. Food to cook. And, of course, the new sign. On Sunday, Christ the King Church — Anglican — became Christ the King Catholic Church. The Towson congregation of about 140 is one of the first groups in the United States to join a new "ordinariate" established for those who want to be Catholic but hold on to Anglican traditions. The largest Anglican church in the country to do so, it follows in the footsteps of Mount Calvary Church in Baltimore and St. Luke's Parish in Bladensburg.

Liberal stances by Anglican leaders, particularly Episcopalians, have driven some clergy and members to the Roman Catholic Church. But Meeks, who studied to become a Catholic priest as a young man, speaks not of rejection but of reunification — becoming one with the "authentic apostolic authority" of the church that dates back 2,000 years.

"We're just overjoyed by this," said the Rev. Msgr. Jeffrey Steenson, who heads the U.S. ordinariate, the equivalent of a diocese but national in scope. As parishioners of all ages scurried past to take their seats for the Mass, he added, "It's such a healthy community — you can see it's full of children."

The parishioners who became Catholics Sunday morning were joining the church for the first time or returning after years apart. A handful of parishioners haven't decided whether to make that leap, though they're remaining in the congregation.

Others left. The 140-member church had about 200 parishioners when it started down the road to Catholicism almost two years ago, losing both those who didn't want to be Catholic and those who opted for a more traditionally Catholic experience.

That loss has been painful, parishioners say. But they add that the transformation from Protestant to Catholic has not been acrimonious — in contrast to the roiling discontent that produced the Church of England more than 450 years ago and that spawned Anglican churches around the world. Some parishioners who went elsewhere return for social events.

"We've still got a good relationship with virtually all who have left," Meeks said.

and 4)--This story, also from The Telegraph from a few months back, about the community left behind by the Anglican Ordinariate:

Members of the congregation at St Michael and All Angels parish church in Croydon, south London, don’t ask for much. A decent sermon, perhaps a few rousing hymns; clean pews; a tidy garden at the back; someone to help with Sunday school. But this month, they need something rather more important: a new vicar, to replace the one who converted to Catholicism and took 69 of his flock with him to a church up the road.

A “Parish priest: vacant” sign now stands outside the towering red-brick church behind West Croydon train station. Seven weeks ago, it housed 100 parishioners and a vicar who had served there for 16 years. Today, St Michael’s has less than half its original congregation, after the Rev Donald Minchew quit his post and was received into the Catholic faith at St Mary’s, 500 yards away.

This extraordinary leap of faith was prompted by the Rev Minchew’s decision to join the Ordinariate, a structure within the Roman Catholic Church that allows Anglicans to enter into full communion while retaining some of their C of E heritage. The practice started last January, when three former Anglican bishops were ordained as Catholic priests, following a decree from Pope Benedict XVI to heal division between the faiths. Since then, dissatisfaction with aspects of Anglican doctrine – including the Church’s attitude towards homosexuality and its willingness to consider female bishops – has led hundreds to take up the offer of conversion.

The Rev Minchew’s reasons for leaving St Michael’s were rooted in his doubts about the Anglican faith. “In the Church of England, you don’t know what the Church believes from one synod to the next,” he said. “I think there is great comfort in the Catholic church: you know what you believe and what the Church teaches.”

But what of those he left behind? St Michael’s is one of many Anglican parishes for which the Ordinariate has meant empty pews, an interregnum and a gaping hole in church life for the congregation.

A collection of centuries-old skeletons excavated in Oxfordshire and stored in a museum are to be reburied as part of a "celebration" mass.

The human remains were found during the extension of a church graveyard in Eynsham, leading to excavations between 1989 and 1992.

Father Martin Flatman, of St Peter's Catholic Church, said he was pleased he could give them a "proper burial".

Six bodies are thought to be monks from the medieval Eynsham Abbey.

The remains of two women and a man have been dated to after the Reformation, and are believed to have been secretly buried in the consecrated ground.

The Catholic church was built on the site of the ancient abbey in the 1940s.

'Rib fractures'

Father Flatman said: "Suddenly it dawned on me that I didn't know where the bodies were. I found out they were in the museum's storage and I applied to have them back.

"As a Catholic we honour the dead and we wouldn't want to leave them, particularly those faithful 16th and 17th Century Catholics who faced persecution."

The finding of those bodies at Eynsham Abbey is another demonstration of what Eamon Duffy indicated in his article in The Telegraph I posted yesterday: for too long, England has ignored its past. In burying those recusant faithful, Father Flatman is reminding England of a time when a Catholic was forced to conform to the national church at birth, at her marriage, and at death.

2)--This interview from Hilary Mantel in The Telegraph:

Mantel was raised a Roman Catholic and educated at convent school.

However, the 59-year-old writer said child abuse scandals involving Roman Catholic priests demonstrated the “cruelty” and “hypocrisy” of the church.

Asked if she would call for a priest on her deathbed, Mantel replied: “No. I might very well call for a Church of England vicar, but I would not call for a Catholic priest.

“I’m one of nature’s Protestants. I should never have been brought up as a Catholic. I think that nowadays the Catholic Church is not an institution for respectable people.”

Which reminds me of the Oscar Wilde comment, "The Catholic Church is for saints and sinners alone. For respectable people, the Anglican Church will do." (Remember that Oscar Wilde became a Catholic on his deathbed.) Francis Phillips responded here in The Catholic Herald. Mantel may think she was being remarkably current and astute ("nowadays") in her comment, but she is ignoring the past five hundred years in England, too--not to mention the Gospel stories of Jesus dining with tax collectors and publicans--they weren't respectable either. For a literate and learned person, she made a most illiterate and ignorant statement.

3)--This story from Maryland:

The Rev. Edward Meeks and his flock attended to a "million and one details" last week in the run-up to a momentous day for their church. People to talk to. Flowers to arrange. Food to cook. And, of course, the new sign. On Sunday, Christ the King Church — Anglican — became Christ the King Catholic Church. The Towson congregation of about 140 is one of the first groups in the United States to join a new "ordinariate" established for those who want to be Catholic but hold on to Anglican traditions. The largest Anglican church in the country to do so, it follows in the footsteps of Mount Calvary Church in Baltimore and St. Luke's Parish in Bladensburg.

Liberal stances by Anglican leaders, particularly Episcopalians, have driven some clergy and members to the Roman Catholic Church. But Meeks, who studied to become a Catholic priest as a young man, speaks not of rejection but of reunification — becoming one with the "authentic apostolic authority" of the church that dates back 2,000 years.

"We're just overjoyed by this," said the Rev. Msgr. Jeffrey Steenson, who heads the U.S. ordinariate, the equivalent of a diocese but national in scope. As parishioners of all ages scurried past to take their seats for the Mass, he added, "It's such a healthy community — you can see it's full of children."

The parishioners who became Catholics Sunday morning were joining the church for the first time or returning after years apart. A handful of parishioners haven't decided whether to make that leap, though they're remaining in the congregation.

Others left. The 140-member church had about 200 parishioners when it started down the road to Catholicism almost two years ago, losing both those who didn't want to be Catholic and those who opted for a more traditionally Catholic experience.

That loss has been painful, parishioners say. But they add that the transformation from Protestant to Catholic has not been acrimonious — in contrast to the roiling discontent that produced the Church of England more than 450 years ago and that spawned Anglican churches around the world. Some parishioners who went elsewhere return for social events.

"We've still got a good relationship with virtually all who have left," Meeks said.

and 4)--This story, also from The Telegraph from a few months back, about the community left behind by the Anglican Ordinariate:

Members of the congregation at St Michael and All Angels parish church in Croydon, south London, don’t ask for much. A decent sermon, perhaps a few rousing hymns; clean pews; a tidy garden at the back; someone to help with Sunday school. But this month, they need something rather more important: a new vicar, to replace the one who converted to Catholicism and took 69 of his flock with him to a church up the road.

A “Parish priest: vacant” sign now stands outside the towering red-brick church behind West Croydon train station. Seven weeks ago, it housed 100 parishioners and a vicar who had served there for 16 years. Today, St Michael’s has less than half its original congregation, after the Rev Donald Minchew quit his post and was received into the Catholic faith at St Mary’s, 500 yards away.

This extraordinary leap of faith was prompted by the Rev Minchew’s decision to join the Ordinariate, a structure within the Roman Catholic Church that allows Anglicans to enter into full communion while retaining some of their C of E heritage. The practice started last January, when three former Anglican bishops were ordained as Catholic priests, following a decree from Pope Benedict XVI to heal division between the faiths. Since then, dissatisfaction with aspects of Anglican doctrine – including the Church’s attitude towards homosexuality and its willingness to consider female bishops – has led hundreds to take up the offer of conversion.

The Rev Minchew’s reasons for leaving St Michael’s were rooted in his doubts about the Anglican faith. “In the Church of England, you don’t know what the Church believes from one synod to the next,” he said. “I think there is great comfort in the Catholic church: you know what you believe and what the Church teaches.”

But what of those he left behind? St Michael’s is one of many Anglican parishes for which the Ordinariate has meant empty pews, an interregnum and a gaping hole in church life for the congregation.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Eamon Duffy Sums It Up

The destruction of most of the libraries, music and art of England was not a religious breakthrough but a cultural calamity

For five centuries England has been in denial about the role of Roman Catholicism in shaping it. The coin in your pocket declares the monarch to be Defender of the Faith. Since 1558 that has meant the Protestant faith, but Henry VIII actually got the title from the Pope for defending Catholicism against Luther. Henry eventually broke with Rome because the Pope refused him a divorce, and along with the papacy went saints, pilgrimage, the monastic life, eventually even the Mass itself – the pillars of medieval Christianity.

To explain that revolution, the Protestant reformers told a story. Henry had rejected not the Catholic Church, but a corrupt pseudo-Christianity which had led the world astray. John Foxe embodied this story unforgettably in his Book of Martyrs, subsidised by the Elizabethan government as propaganda against Catholicism at home and abroad. For Foxe, Queen Elizabeth was her country’s saviour, and the Reformation itself the climax of an age-old struggle between God, represented by the monarch, and the devil, represented by the Pope. . . .

It is time to look again at the Reformation story. There was nothing inevitable about the Reformation. The heir to the throne is uneasy about swearing to uphold the Protestant faith, and it seems less obvious than it once did that the religion which gave us the Wilton Diptych and Westminster Abbey, or the music of Tallis, Byrd and Elgar, is intrinsically un-English. The destruction of the monasteries and most of the libraries, music and art of medieval England now looks what it always was – not a religious breakthrough, but a cultural calamity.

Read the rest of The Telegraph article here. Duffy's new book, Saints, Sacrilege and Sedition: Religion and Conflict in the Tudor Reformations is due out in the U.S. on August 2!! The Independent in the U.K. has this review:

Even in the potentially disjointed format of a collection of essays, there is something compelling and even thrilling about Duffy's combination of cutting-edge historical scholarship and effortless prose. At the heart of the story he tells is an account of the deep, deep roots that Catholicism had in England before, during and for a long time after Henry's decision to dispense with Rome. As one who grew up Catholic at the tail end of a 400-year period when my co-believers were routinely persecuted and regarded as somehow foreign, or unEnglish, it is remarkable to learn how much my faith is home-grown, part of the landscape, and of the nation's enduring religious sensibility, even if most traces of that have been obliterated and then denied. In Duffy's bottom-up approach to history, as in the fragments of stained glass that have survived in the otherwise clear panes in Salle church, there is a much bigger, bolder story.

It is time to look again at the Reformation story. There was nothing inevitable about the Reformation. The heir to the throne is uneasy about swearing to uphold the Protestant faith, and it seems less obvious than it once did that the religion which gave us the Wilton Diptych and Westminster Abbey, or the music of Tallis, Byrd and Elgar, is intrinsically un-English. The destruction of the monasteries and most of the libraries, music and art of medieval England now looks what it always was – not a religious breakthrough, but a cultural calamity.

Read the rest of The Telegraph article here. Duffy's new book, Saints, Sacrilege and Sedition: Religion and Conflict in the Tudor Reformations is due out in the U.S. on August 2!! The Independent in the U.K. has this review:

Even in the potentially disjointed format of a collection of essays, there is something compelling and even thrilling about Duffy's combination of cutting-edge historical scholarship and effortless prose. At the heart of the story he tells is an account of the deep, deep roots that Catholicism had in England before, during and for a long time after Henry's decision to dispense with Rome. As one who grew up Catholic at the tail end of a 400-year period when my co-believers were routinely persecuted and regarded as somehow foreign, or unEnglish, it is remarkable to learn how much my faith is home-grown, part of the landscape, and of the nation's enduring religious sensibility, even if most traces of that have been obliterated and then denied. In Duffy's bottom-up approach to history, as in the fragments of stained glass that have survived in the otherwise clear panes in Salle church, there is a much bigger, bolder story.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

The Priest-Martyr of Westminster

Father John Southworth came from a Lancashire family who lived at Samlesbury Hall. They chose to pay heavy fines rather than give up the Catholic faith.

He studied at the English College in Douai, now in northern France, (and then moved to Hertfordshire, St Edmunds College) and was ordained priest before he returned to England. Imprisoned and sentenced to death for professing the Catholic faith, he was later deported to France, with the help of Queen Henrietta Maria--he had at first been imprisoned with St. Edmund Arrowsmith in Lancaster and witnessed that martyr's death; then he was moved to The Clink in London and then exiled. Once more he returned to England and lived in Clerkenwell, London, during a plague epidemic, working along with St. Henry Morse. He assisted and converted the sick in Westminster and was arrested again.

He was again arrested under the Interregnum and was tried at the Old Bailey under Elizabethan anti-priest legislation . He pleaded guilty to exercising the priesthood and was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. At his execution at Tyburn, London, he suffered the full pains of his sentence and was hanged, drawn and quartered. He was allowed to speak before his sentence was carried out. Among his last words:

“My faith and obedience to my superiors is all the treason charged against me; nay, I die for Christ’s law, which no human law, by whomsoever made, ought to withstand or contradict… To follow His holy doctrine and imitate His holy death, I willingly suffer at present; this gallows I look on as His Cross, which I gladly take to follow my Dear Saviour…I plead not for myself…but for you poor persecuted Catholics whom I leave behind me.

"My faith is my crime, the performance of my duty the occasion of my condemnation. I confess I am a great sinner; against God I have offended, but am innocent of any sin against man, I mean the Commonwealth, and the present Government."

The Venetian Secretary reported on his execution: he was hung, and was not dead when the executioner "cut out his heart and entrails and threw them into a fire kindled for the purpose, the body being quartered . . . Such is the inhuman cruelty used towards the English Catholic religious."

The Spanish ambassador returned his corpse to Douai for burial. His corpse was sewn together and parboiled, to preserve it. Following the French Revolution, his body was buried in an unmarked grave for its protection. The grave was discovered in 1927 and his remains were returned to England. They are now kept in the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs in Westminster Cathedral in London. He was beatified in 1929. In 1970, he was canonized by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. His feast day is 27 June but this is only celebrated in the Westminster diocese.

He studied at the English College in Douai, now in northern France, (and then moved to Hertfordshire, St Edmunds College) and was ordained priest before he returned to England. Imprisoned and sentenced to death for professing the Catholic faith, he was later deported to France, with the help of Queen Henrietta Maria--he had at first been imprisoned with St. Edmund Arrowsmith in Lancaster and witnessed that martyr's death; then he was moved to The Clink in London and then exiled. Once more he returned to England and lived in Clerkenwell, London, during a plague epidemic, working along with St. Henry Morse. He assisted and converted the sick in Westminster and was arrested again.

He was again arrested under the Interregnum and was tried at the Old Bailey under Elizabethan anti-priest legislation . He pleaded guilty to exercising the priesthood and was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. At his execution at Tyburn, London, he suffered the full pains of his sentence and was hanged, drawn and quartered. He was allowed to speak before his sentence was carried out. Among his last words:

“My faith and obedience to my superiors is all the treason charged against me; nay, I die for Christ’s law, which no human law, by whomsoever made, ought to withstand or contradict… To follow His holy doctrine and imitate His holy death, I willingly suffer at present; this gallows I look on as His Cross, which I gladly take to follow my Dear Saviour…I plead not for myself…but for you poor persecuted Catholics whom I leave behind me.

"My faith is my crime, the performance of my duty the occasion of my condemnation. I confess I am a great sinner; against God I have offended, but am innocent of any sin against man, I mean the Commonwealth, and the present Government."

The Venetian Secretary reported on his execution: he was hung, and was not dead when the executioner "cut out his heart and entrails and threw them into a fire kindled for the purpose, the body being quartered . . . Such is the inhuman cruelty used towards the English Catholic religious."

The Spanish ambassador returned his corpse to Douai for burial. His corpse was sewn together and parboiled, to preserve it. Following the French Revolution, his body was buried in an unmarked grave for its protection. The grave was discovered in 1927 and his remains were returned to England. They are now kept in the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs in Westminster Cathedral in London. He was beatified in 1929. In 1970, he was canonized by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. His feast day is 27 June but this is only celebrated in the Westminster diocese.

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Ford Madox Ford, RIP

The English author Ford Madox Ford died on June 26, 1939. He is best known for his novel, The Good Soldier and The Fifth Queen, a historical novel about Katherine Howard, Henry VIII's fifth wife, whom he had beheaded for infidelity. He became Catholic when a teenager. Ford worked with Joseph Conrad on several works (The Shifting of the Fire, for example), and collaborated with other authors as he edited the English Review.

The English author Ford Madox Ford died on June 26, 1939. He is best known for his novel, The Good Soldier and The Fifth Queen, a historical novel about Katherine Howard, Henry VIII's fifth wife, whom he had beheaded for infidelity. He became Catholic when a teenager. Ford worked with Joseph Conrad on several works (The Shifting of the Fire, for example), and collaborated with other authors as he edited the English Review.Ralph McInerny offers this overview of Ford's life and achievements.

Vintage Books reissued The Fifth Queen last year, hoping to take advantage of the Wolf Hall publishing phenomenon:

The pretty re-issue of Ford Madox Ford’s great “Fifth Queen” trilogy of slim novels, written between 1906 and 1908, conform to no anniversary except the hope of money: Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall is a rising tide that might well float a few Tudor galleons, and it shares with Ford that most memorable character, Thomas Cromwell. The Cromwell stalking through both Mantel’s book and Ford’s trilogy (collected by Vintage – same as by Ecco back in 1986) is much the same man – blunt yet cunning, brutal yet sensitive, and possessing a clearer eye for absolute rule than the corpulent king he serves:

‘God is above us all,’ he answered. ‘But there is no room for two heads of a State, and in a State is room but for one army. I will have my King so strong that no Pope no priest no noble no people shall here have speech or power. So it is now; I have so made it, the King helping me. Before I came this was a distracted State; the King’s writ ran not in the east, not in the west, not in the north, and hardly in the south parts. Now no lord nor no bishop nor no Pope raises head against him here. And, God willing, in all the world no prince shall stand but by the grace of this King’s Highness. This land shall have the wealth of all the world; this King shall guide this land. There shall be rich husbandmen paying no toll to priests, but to the King alone; there shall be wealthy merchants paying no tax to any prince nor emperor, but only to this King. The King’s court shall redress all wrongs; the King’s voice shall be omnipotent in the council of the princes.’

Seems a little odd that the Vintage cover should depict the Princess Mary, Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon's daughter--but then, there are no reliable portraits of Henry VIII's fifth queen.

Monday, June 25, 2012

St. Thomas More and Torture

Wolf Hall, the first volume in Hilary Mantel's trilogy of novels about Thomas Cromwell casts St. Thomas More in an unflattering light, one that reviewers might be relishing. The Mirror of Justice blog posted this discussion on whether Chancellor More, in the process of enforcing England's heresy laws, used torture:

This past Sunday's NY Times Book Review includes a review of Bring Up the Bodies, the much-anticipated sequel to Hilary Mantel's Booker Prize-winning novel Wolf Hall about Henry VIII and his court. The hero, of sorts, in Mantel's novels about the period is Thomas Cromwell, whom Mantel sets off against Thomas More (depicted in Wolf Hall as an eager torturer of Protestants). The reviewer, Charles McGrath (former editor of the Book Review), writes: "In Mantel’s version, More is no saint, as he almost certainly was not in real life: he’s fussily pious, stiff-necked and unnaturally fond of torturing heretics."

Let me be clear: Thomas More generally shared in the prejudices of his age and was complicit in practices (most especially the use of state coercion with regard to religious belief) that we would today regard as morally odious. That's just to say that he lived in the early sixteenth century and not the early twenty-first century, and we could have a lively discussion about how the Catholic Church should assess the sanctity of people with the benefit of historical and moral hindsight.

And Michael Moreland, the author of the post, goes on:

But a couple of further observations about the review:

1. McGrath's statement (characterizing Mantel's view) that More was "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked" is open to debate based on the contemporaneous accounts of More, though I'd simply make the point for now that More's canonization in 1935 was largely based on the manner of his death--the fact that More (alongside John Fisher and later joined by the 1970 canonization of 40 martyrs and the 1987 beatification of 85 martyrs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in England) suffered martyrdom for the Catholic faith rather than acquiescing to Henry VIII's assertion of power over the Church in England.

2. It's another thing altogether to make the slanderous claim that More was "unnaturally fond of torturing heretics," for the scholarly consensus is that there is no historical evidence that More engaged in torture. As summarized by John Guy in The Public Career of Sir Thomas More (Yale, 1980), "Serious analysis precludes the repetition of protestant stories that Sir Thomas flogged heretics against a tree in his garden at Chelsea. It must exclude, too, the accusations of illegal imprisonment made against More by John Field and Thomas Phillips. Much vaunted by J.A. Froude, such charges are unsupported by independent proof. More indeed answered them in his Apology with emphatic denial. None has ever been substantiated, and we may hope that they were all untrue" (165-66). See also G.R. Elton, Studies in Tudor and Stuart Politics and Government, Papers and Reviews 1946-1972, Volume 1, 158 ("It is necessary to be very clear about More's reaction to the changes in religion which he saw all around him. No doubt, the more scurrilous stories of his personal ill-treatment of accused heretics have been properly buried, but that is not to make him into a tolerant liberal.").

I posted the following comment about the charge that St. Thomas More was "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked", which I find ridiculous, given the "contemporaneous accounts of More's life" with the examples of his humor, charity, and friendship that even detractors have to acknowledge. I'd also have to say that the comments about St. Thomas More in a review about a book in which he does not appear are rather gratuitous. The reviewer just wants to attack More since More is the patron saint of conscience, politicians and statesmen:

Beyond the issue of St. Thomas More and the persecution of heretics, how can a man be called "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked" who expresses the hope that he and his judges will meet merrily in Heaven?--"More have I not to say, my lords, but that like as the blessed apostle Saint Paul, as we read in the Acts of the Apostles, was present and consented to the death of Saint Stephen, and kept their clothes that stoned him to death, and yet be they now twain holy saints in heaven, and shall continue there friends forever: so I verily trust and shall therefore right heartily pray, that though your lordships have now in earth been judges to my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together to our everlasting salvation."

Desiderius Erasmus, who could not abide fussy piety, would certainly disagree with Mantel's characterization of "More"--"Friendship he seems born and designed for; no one is more open-hearted in making friends or more tenacious in keeping them, nor has he any fear of that plethora of friendships against which Hesiod warns us.... Nobody is less swayed by public opinion, and yet nobody is closer to the feelings of ordinary men."

This past Sunday's NY Times Book Review includes a review of Bring Up the Bodies, the much-anticipated sequel to Hilary Mantel's Booker Prize-winning novel Wolf Hall about Henry VIII and his court. The hero, of sorts, in Mantel's novels about the period is Thomas Cromwell, whom Mantel sets off against Thomas More (depicted in Wolf Hall as an eager torturer of Protestants). The reviewer, Charles McGrath (former editor of the Book Review), writes: "In Mantel’s version, More is no saint, as he almost certainly was not in real life: he’s fussily pious, stiff-necked and unnaturally fond of torturing heretics."

Let me be clear: Thomas More generally shared in the prejudices of his age and was complicit in practices (most especially the use of state coercion with regard to religious belief) that we would today regard as morally odious. That's just to say that he lived in the early sixteenth century and not the early twenty-first century, and we could have a lively discussion about how the Catholic Church should assess the sanctity of people with the benefit of historical and moral hindsight.

And Michael Moreland, the author of the post, goes on:

But a couple of further observations about the review:

1. McGrath's statement (characterizing Mantel's view) that More was "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked" is open to debate based on the contemporaneous accounts of More, though I'd simply make the point for now that More's canonization in 1935 was largely based on the manner of his death--the fact that More (alongside John Fisher and later joined by the 1970 canonization of 40 martyrs and the 1987 beatification of 85 martyrs from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in England) suffered martyrdom for the Catholic faith rather than acquiescing to Henry VIII's assertion of power over the Church in England.

2. It's another thing altogether to make the slanderous claim that More was "unnaturally fond of torturing heretics," for the scholarly consensus is that there is no historical evidence that More engaged in torture. As summarized by John Guy in The Public Career of Sir Thomas More (Yale, 1980), "Serious analysis precludes the repetition of protestant stories that Sir Thomas flogged heretics against a tree in his garden at Chelsea. It must exclude, too, the accusations of illegal imprisonment made against More by John Field and Thomas Phillips. Much vaunted by J.A. Froude, such charges are unsupported by independent proof. More indeed answered them in his Apology with emphatic denial. None has ever been substantiated, and we may hope that they were all untrue" (165-66). See also G.R. Elton, Studies in Tudor and Stuart Politics and Government, Papers and Reviews 1946-1972, Volume 1, 158 ("It is necessary to be very clear about More's reaction to the changes in religion which he saw all around him. No doubt, the more scurrilous stories of his personal ill-treatment of accused heretics have been properly buried, but that is not to make him into a tolerant liberal.").

I posted the following comment about the charge that St. Thomas More was "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked", which I find ridiculous, given the "contemporaneous accounts of More's life" with the examples of his humor, charity, and friendship that even detractors have to acknowledge. I'd also have to say that the comments about St. Thomas More in a review about a book in which he does not appear are rather gratuitous. The reviewer just wants to attack More since More is the patron saint of conscience, politicians and statesmen:

Beyond the issue of St. Thomas More and the persecution of heretics, how can a man be called "fussily pious" and "stiff-necked" who expresses the hope that he and his judges will meet merrily in Heaven?--"More have I not to say, my lords, but that like as the blessed apostle Saint Paul, as we read in the Acts of the Apostles, was present and consented to the death of Saint Stephen, and kept their clothes that stoned him to death, and yet be they now twain holy saints in heaven, and shall continue there friends forever: so I verily trust and shall therefore right heartily pray, that though your lordships have now in earth been judges to my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together to our everlasting salvation."

Desiderius Erasmus, who could not abide fussy piety, would certainly disagree with Mantel's characterization of "More"--"Friendship he seems born and designed for; no one is more open-hearted in making friends or more tenacious in keeping them, nor has he any fear of that plethora of friendships against which Hesiod warns us.... Nobody is less swayed by public opinion, and yet nobody is closer to the feelings of ordinary men."

Sunday, June 24, 2012

St. John the Baptist and The English Reformation

Today is the Solemnity of the Birth of St. John the Baptist. Only two other birthdays are celebrated on the Church Calendar: The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the The Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Otherwise, saints and blessed are remembered on the dates of the deaths (or perhaps the "translation" of their remains or some other important date--not usually their birthdate). The saint's day of earthly death is the beginning of their eternal life in Heaven. This site offers the reason for honoring St. John the Baptist on his birhday--because he was cleansed from Original Sin, baptised as it were, when Mary visited her cousin Elizabeth and he leapt in his mother's womb when the unborn Jesus in Mary's womb came near him. St. Augustine pointed to this understanding of St. John the Baptist's holy birth. (St. John the Baptist has another feast, that of his Beheading, on August 29, and a friend of mine pointed out that the Orthodox churches honor St. John the Baptist even more often: September 23 —Conception of St. John the Forerunner; January 7 — The Synaxis of St. John the Forerunner; February 24 — First and Second Finding of the Head of St. John the Forerunner; May 25 — Third Finding of the Head of St. John the Forerunner; June 24 — Nativity of St. John the Forerunner, and August 29 — The Beheading of St. John the Forerunner!)

Devotion to St. John the Baptist is ancient in the Church and his Nativity was celebrated with a vigil and with bonfires on the feast. This site points out a pilgrimage site in Norfolk before the English Reformation demonstrating devotion to the saint as a martyr, as it had a replica of the head of St. John the Baptist. The image was destroyed at some point during the Reformation, of course.

Another mark of devotion to St. John the Baptist in England was the presence of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John in England, suppressed by Henry VIII. He had Sir Thomas Dingley and Sir Adrian Fortescue executed under Attainder in July of 1539 and seized the order's property in England:

Devotion to St. John the Baptist is ancient in the Church and his Nativity was celebrated with a vigil and with bonfires on the feast. This site points out a pilgrimage site in Norfolk before the English Reformation demonstrating devotion to the saint as a martyr, as it had a replica of the head of St. John the Baptist. The image was destroyed at some point during the Reformation, of course.

Another mark of devotion to St. John the Baptist in England was the presence of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John in England, suppressed by Henry VIII. He had Sir Thomas Dingley and Sir Adrian Fortescue executed under Attainder in July of 1539 and seized the order's property in England:

The Order in Britain

From the beginning the Order grew rapidly and was given land throughout Western Europe. Its estates were managed by small groups of brothers and sisters who lived in communities that provided resources to the headquarters of the Order. These communities were gradually gathered into provinces called Priories or Grand Priories.

In Britain these estates were first administered from one of the communities (called a Commandery) at Clerkenwell, London from about 1140 and the original Priory Church was built at the same time.

However, over time, the extensive amount of land the Order owned in Britain meant that it needed to be managed by several different Commanderies. In 1185 the Commandery at Clerkenwell became a Priory, and had responsibility for Commanderies that had been set up in Scotland and Wales as well as the ones in England. Ireland became a separate Priory.

Henry VIII

In 1540 the Order was suppressed by King Henry VIII, as part of the process known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It was restored and incorporated by Queen Mary I in 1557, but when Queen Elizabeth I again confiscated all its estates in 1559 she did so without annulling its incorporation. These acts by English Sovereigns did not directly affect the Order in Scotland, but the influence of the Reformation ended the Order’s activities there in about 1564. The Order in Britain then fell into abeyance.

One may, today, however visit the Museum of the Order of St. John in London today.

The provisions of Elizabeth I's Act of Uniformity of 1559 all took effect on this feast:

Where at the death of our late sovereign lord King Edward VI there remained one uniform order of common service and prayer, and of the administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies in the Church of England, which was set forth in one book, intituled: The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of Sacraments, and other rites and ceremonies in the Church of England; authorized by Act of Parliament holden in the fifth and sixth years of our said late sovereign lord King Edward VI, intituled: An Act for the uniformity of common prayer, and administration of the sacraments; the which was repealed and taken away by Act of Parliament in the [Page 459] first year of the reign of our late sovereign lady Queen Mary, to the great decay of the due honour of God, and discomfort to the professors of the truth of Christ's religion:

Be it therefore enacted by the authority of this present Parliament, that the said statute of repeal, and everything therein contained, only concerning the said book, and the service, administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies contained or appointed in or by the said book, shall be void and of none effect, from and after the feast of the Nativity of St. John Baptist next coming; and that the said book, with the order of service, and of the administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies, with the alterations and additions therein added and appointed by this statute, shall stand and be, from and after the said feast of the Nativity of St. John Baptist, in full force and effect, according to the tenor and effect of this statute; anything in the aforesaid statute of repeal to the contrary notwithstanding.

Finally, the Catholic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Norwich, pictured above (source is Wikipedia commons) was built after Catholic Emancipation and Restoration the nineteenth century, and dedicated as the Cathedral in 1976:

The Cathedral of St John the Baptist is a fine example of the great Victorian Gothic Revival. Designed by George Gilbert Scott Junior, it was the generous gift to the Catholics of Norwich of Henry Fitzalan Howard as a thank-offering for his first marriage to Lady Flora Abney-Hastings. Duke Henry, following an approach by Canon Richard Duckett, commissioned the building and took a keen interest in every aspect of its design from its initial conception in the early 1870s to its completion and dedication in 1910. Until 1976 when it became the Cathedral of the new Diocese of East Anglia, this great church was believed to be the largest parish church in England.

Now a Grade 1 listed building, the Cathedral of St John the Baptist is one of Norwich’s iconic buildings, rising above the city skyline. Its external grandeur and magnificent interior, especially the fine stonework and beautiful stained glass make it well worth a visit for those interested in architectural history; they will also find an inspiring and tranquil place of prayer.

St. John the Baptist, the Forerunner, Prophet and Martyr, pray for us!

The provisions of Elizabeth I's Act of Uniformity of 1559 all took effect on this feast:

Where at the death of our late sovereign lord King Edward VI there remained one uniform order of common service and prayer, and of the administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies in the Church of England, which was set forth in one book, intituled: The Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of Sacraments, and other rites and ceremonies in the Church of England; authorized by Act of Parliament holden in the fifth and sixth years of our said late sovereign lord King Edward VI, intituled: An Act for the uniformity of common prayer, and administration of the sacraments; the which was repealed and taken away by Act of Parliament in the [Page 459] first year of the reign of our late sovereign lady Queen Mary, to the great decay of the due honour of God, and discomfort to the professors of the truth of Christ's religion:

Be it therefore enacted by the authority of this present Parliament, that the said statute of repeal, and everything therein contained, only concerning the said book, and the service, administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies contained or appointed in or by the said book, shall be void and of none effect, from and after the feast of the Nativity of St. John Baptist next coming; and that the said book, with the order of service, and of the administration of sacraments, rites, and ceremonies, with the alterations and additions therein added and appointed by this statute, shall stand and be, from and after the said feast of the Nativity of St. John Baptist, in full force and effect, according to the tenor and effect of this statute; anything in the aforesaid statute of repeal to the contrary notwithstanding.

Finally, the Catholic Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Norwich, pictured above (source is Wikipedia commons) was built after Catholic Emancipation and Restoration the nineteenth century, and dedicated as the Cathedral in 1976:

The Cathedral of St John the Baptist is a fine example of the great Victorian Gothic Revival. Designed by George Gilbert Scott Junior, it was the generous gift to the Catholics of Norwich of Henry Fitzalan Howard as a thank-offering for his first marriage to Lady Flora Abney-Hastings. Duke Henry, following an approach by Canon Richard Duckett, commissioned the building and took a keen interest in every aspect of its design from its initial conception in the early 1870s to its completion and dedication in 1910. Until 1976 when it became the Cathedral of the new Diocese of East Anglia, this great church was believed to be the largest parish church in England.

Now a Grade 1 listed building, the Cathedral of St John the Baptist is one of Norwich’s iconic buildings, rising above the city skyline. Its external grandeur and magnificent interior, especially the fine stonework and beautiful stained glass make it well worth a visit for those interested in architectural history; they will also find an inspiring and tranquil place of prayer.

St. John the Baptist, the Forerunner, Prophet and Martyr, pray for us!

Saturday, June 23, 2012

St. Thomas Garnet, SJ (an Allegiance Oath Martyr)

St. Thomas Garnet, SJ was an alumnus of the seminary in Valladolid, Spain:

ST. Thomas GARNET SJ son of Richard Garnet Confessor of the Faith, and nephew of Father Henry Garnet SJ martyr, was born in London in 1574.

For some time he was page to the Count of Arundel, until, in the year 1594, at the age of sixteen, he entered the college at St. Omer in the Low Countries.

Two years after, he was ordered to the college of St. Alban at VALLADOLID, where he studied for four years. In the same city he was ordained a priest, and from there returned to England.

In 1604 he was admitted to the Society of Jesus by his uncle (the local superior of the Jesuits), but upon attempting to leave England to begin his noviciate at Louvain, he was stopped and incarcerated in the Gatehouse jail at Westminster, and later in the Tower of London. He was banished in the year 1606. [Note that authorities wanted him to give information about his uncle's involvement in the Gunpowder Plot.]

Shortly afterwards, he returned surreptitiously to England, where he was betrayed for being a priest. He was interrogated before the Protestant bishop of London on the 17th of November 1607, but refused to answer his questions, neither was he disposed to make the new oath of loyalty, because its contents were against the Catholic Faith. Having been intensively interrogated already for the bishop by Sir Thomas Wade, the superintendent of the keep and a very cruel torturer of priests, Father Garnet was moved to the Old Bailey prison.

Shortly afterwards, he was processed and condemned for his priesthood. While in jail, some Catholics provided him with means of escaping, but he refused, choosing rather to obey an interior voice that said to him "noli fugere".

He was stripped, hung, drawn and quartered at Tyburn (London) on the 23rd of June 1608.On the 25th of October 1970, he was solemnly canonised by Pope Paul VI.

On the scaffold he announced that he was the happiest man alive that day. His steadfastness in facing death impressed the crowds, so he was dead before quartering and beheading.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Saints John Fisher and Thomas More

Today is the second day of the U.S. Bishops' "Fortnight for Freedom" and the Feast of St. John Fisher and St. Thomas More, martyrs, sharing the same feast day. St. John Fisher was executed on June 22, 1535, St. Thomas More on July 6, 1535. Both men's holiness was remarkable at the time of their living and yet they were not canonized until four hundred years later in 1935, on May 19 by Pope Pius XI. Without a free and established Catholicism in England, the deovtion and the cause for all the English martyrs took a long time to develop.

Today is the second day of the U.S. Bishops' "Fortnight for Freedom" and the Feast of St. John Fisher and St. Thomas More, martyrs, sharing the same feast day. St. John Fisher was executed on June 22, 1535, St. Thomas More on July 6, 1535. Both men's holiness was remarkable at the time of their living and yet they were not canonized until four hundred years later in 1935, on May 19 by Pope Pius XI. Without a free and established Catholicism in England, the deovtion and the cause for all the English martyrs took a long time to develop.Pope Pius XI began his homily at the canonization Mass with the some historical context:

From time to time new heresies make their appearance and, under the guise of truth, gain strength and popularity; but the seamless garment of Christ can never be rent in twain. Unbelievers and enemies of the Catholic faith, blinded by presumption, may indeed constantly renew their violent attacks against the Christian name, but in wresting from the bosom of the militant Church those whom they put to death, they become the instruments of their martyrdom and of their heavenly glory. No less beautiful than true are the words of St. Leo the Great: “The religion of Christ, founded on the mystery of the Cross, cannot be destroyed by any sort of cruelty; persecutions do not weaken, they strengthen the Church. The field of the Lord is ever ripening with new harvests, while the grains shaken loose by the tempest take root and are multiplied.”

Speaking of the two martyrs, Pope Pius said that St. John Fisher "was gifted by nature with a most gentle disposition, thoroughly versed in both sacred and profane lore, so distinguished himself among his contemporaries by his wisdom and his virtue that under the patronage of the King of England himself, he was elected Bishop of Rochester. In the fulfilment of this high office so ardent was he in his piety towards God, and in charity towards his neighbour, and so zealous in defending the integrity of Catholic doctrine, that his episcopal residence seemed rather a Church and a University for studies than a private dwelling." Of St. Thomas More he said, "he was no less distinguished for his desire of Christian perfection and his zeal for the salvation of souls. Of this we have testimony in the ardour of his prayer, in the fervour with which he recited, whenever he could, even the Canonical Hours, in the practice of those penances by which he kept his body in subjection, and finally in the numerous and renowned accomplishments of both the spoken and the written word which he achieved for the defence of the Catholic faith and for the safeguarding of Christian morality." The pope also took the opportunity to pray for the conversion of England:

We desire moreover that with your ardent prayers, invoking the patronage of the new Saints, you ask of the Lord that which is so dear to Our heart, namely that England, in the words of St. Paul, "meditating the happy consummation which crowned the life" of those two martyrs, may "follow them in their faith," and return to the Father’s house "in the unity of faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God."

More usually gets more attention, because of the A Man for All Seasons fame (which has its own pitfalls), but Fisher, with even deeper links to the Tudor family (preacher at the funerals of both Henry VIII's father and grandmother) and more consistent and open opposition to Henry's plans to take over the Church and push through his marital arrangement, is just as interesting. He was a humanist, a bishop, a serious defender of Church teaching, and an admired churchman in his lifetime. In his death he demonstrated the same dignity and holiness:

When he came out of the Tower, a summer morning's mist hung over the river, wreathing the buildings in a golden haze. Two of the Lieutenant's men carried him in a chair to the gate, and there they set him down, while waiting for the Sheriffs. The cardinal stood up and leaning his shoulder against a wall for support, opened the little New Testament he carried in his hand. "O Lord," he said, so that all could hear him, "this is the last time I shall ever open this book. Let some comforting place now chance to me whereby I, Thy poor servant, may glorify Thee in my last hour"----and looking down at the page, he read:

Now this is etemal life: that they may know Thee, the one true God, and Jesus Christ Whom Thou has sent I have glorified Thee on earth: I have finished the work which Thou gavest me to do (John, 17:3-4).

Whereupon he shut the book, saying: "Here is even learning enough for me to my life's end." His lips were moving in prayer, as they carried him to Tower Hill. And when they reached the scaffold, the rough men of his escort offered to help him up the ladder. But he smiled at them: "Nay, masters, now let me alone, ye shall see me go up to my death well enough myself; without help." And forthwith he began to climb, almost nimbly. As he reached the top the sun appeared from behind the clouds, and its light shone upon his face. He was heard to murmur some words from Psalm 33: Accedite ad eum, etilluminamim, et facies vestræ non confundentur. The masked headsman knelt----as the custom was----to ask his pardon. And again the cardinal's manliness dictated every word of his answer: "I forgive thee with all my heart, and I trust on Our Lord Thou shalt see me die even lustily." Then they stripped him of his gown and furred tippet, and he stood in his doublet and hose before the crowd which had gathered to see his death. A gasp of pity went up at the sight of his "long, lean, slender body, nothing in manner but skin and bones . . . the flesh clean wasted away; and a very image of death, and as one might say, death in a man's shape and using a man's voice." He was offered a final chance to save his life by acknowledging the royal supremacy, but the Saint turned to the crowd, and from the front of the scaffold, he spoke these words:

Christian people, I am come hither to die for the faith of Christ's Catholic Church, and I thank God hitherto my courage hath served me well thereto, so that yet hitherto I have not feared death; wherefore I desire you help me and assist me with your prayers, that at the very point and instant of my death's stroke, and in the very moment of my death, I then faint not in any point of the Catholic Faith for fear; and I pray God save the king and the realm, and hold His holy hand over it, and send the king a good counsel.

The power and resonance of his voice, the courage of his spirit triumphing over the obvious weakness of his body, amazed them all, and a murmur of admiration was still rustling the crowd when they saw him go down on his knees and begin to pray. They stood in awed silence while he said the Te Deum in praise of God, and the Psalm In Thee O Lord have I put my trust, the humble request for strength beyond his own. Then he signed to the executioner to bind his eyes. For a moment more he prayed, hands and heart raised to Heaven. Then he lay down and put his wasted neck upon the low block. The executioner, who had been standing back, took one quick step forward, raised his axe and with a single blow cut off his head. So copious a stream of blood poured from the neck that those present wondered how it could have come from so thin and wasted a frame. There was certainly Divine irony in the fact that 22 June, the date of the execution, was the Feast of St. Alban, the first Martyr for the Faith in Britain. If the king had realized this he would certainly have arranged for the execution of Cardinal Fisher to take place on another day.

Regarding that last sentence in Michael Davies' account of Fisher's death--Henry VIII had no good choice for a date since he was set on executing this good Cardinal Bishop: June 23 was the Vigil of and June 24 was the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist! Fisher had identified himself with St. John the Baptist explicitly [meaning that Henry VIII was Herod and Anne Boleyn was Herodias].

I will be on the Son Rise Morning Show from Sacred Heart Radio in Cincinnati broadcast on the EWTN radio network this morning to discuss this feast day, focusing on St. John Fisher and St. Thomas More in the context of this Fortnight for Freedom--at 7:45 a.m. Eastern/6:45 a.m. Central.

Thursday, June 21, 2012

Honesty Under Oath: Saint John Rigby, layman

From the Catholic Encyclopedia comes this story of today's martyr:

b. about 1570 at Harrocks Hall, Eccleston, Lancashire; executed at St. Thomas Waterings, 21 June, 1600. He was the fifth or sixth son of Nicholas Rigby, by Mary, daughter of Oliver Breres of Preston. In the service of Sir Edmund Huddleston, at a time when his daughter, Mrs. Fortescue, being then ill, was cited to the Old Bailey for recusancy, Rigby appeared on her behalf; compelled to confess himself a Catholic, he was sent to Newgate. The next day, 14 February, 1599 or 1600, he signed a confession, that, since he had been reconciled by the martyr, John Jones the Franciscan, in the Clink some two or three years previously, he had declined to go to church. He was then chained and remitted to Newgate, till, on 19 February, he was transferred to the White Lion. On the first Wednesday in March (which was the 4th and not, as the martyr himself supposes, the 3rd) he was brought to the bar, and in the afternoon given a private opportunity to conform. The next day he was sentenced for having been reconciled; but was reprieved till the next sessions. On 19 June he was again brought to the bar, and as he again refused to conform, he was told that his sentence must be carried out. On his way to execution, the hurdle was stopped by a Captain Whitlock, who wished him to conform and asked him if he were married, to which the martyr replied, "I am a bachelor; and more than that I am a maid", and the captain thereupon desired his prayers. The priest, who reconciled him, had suffered on the same spot 12 July, 1598.

[Note: Both John Rigby and the Franciscan priest, John Jones, were canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.]

b. about 1570 at Harrocks Hall, Eccleston, Lancashire; executed at St. Thomas Waterings, 21 June, 1600. He was the fifth or sixth son of Nicholas Rigby, by Mary, daughter of Oliver Breres of Preston. In the service of Sir Edmund Huddleston, at a time when his daughter, Mrs. Fortescue, being then ill, was cited to the Old Bailey for recusancy, Rigby appeared on her behalf; compelled to confess himself a Catholic, he was sent to Newgate. The next day, 14 February, 1599 or 1600, he signed a confession, that, since he had been reconciled by the martyr, John Jones the Franciscan, in the Clink some two or three years previously, he had declined to go to church. He was then chained and remitted to Newgate, till, on 19 February, he was transferred to the White Lion. On the first Wednesday in March (which was the 4th and not, as the martyr himself supposes, the 3rd) he was brought to the bar, and in the afternoon given a private opportunity to conform. The next day he was sentenced for having been reconciled; but was reprieved till the next sessions. On 19 June he was again brought to the bar, and as he again refused to conform, he was told that his sentence must be carried out. On his way to execution, the hurdle was stopped by a Captain Whitlock, who wished him to conform and asked him if he were married, to which the martyr replied, "I am a bachelor; and more than that I am a maid", and the captain thereupon desired his prayers. The priest, who reconciled him, had suffered on the same spot 12 July, 1598.

[Note: Both John Rigby and the Franciscan priest, John Jones, were canonized by Pope Paul VI in 1970 among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.]

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

With Ropes Around Their Necks, An Offer of a Pardon

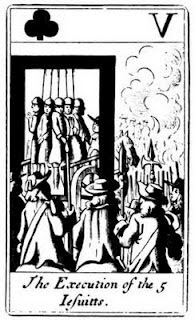

Today is the anniversary of the martyrdoms of five Jesuit Popish Plot Martyrs on June 20, 1679, who died as a result of the false, perjurous claims there was a vast, Jesuit, Catholic-wing conspiracy to assassinate Charles II and bring the Catholic Duke of York, James, his brother to the throne. Oates convinced the Whigs in Parliament that he knew who was in on this plot and he was given the authority to round up the suspects. At the trials for his accused, any witnesses they brought forward would be discounted by the Prosecution and the Judge, because, of course, they were also Catholics and if not in on the plot were probably in favor of the plot! After one of these manifestly unfair trials, five Jesuits were martyred on June 20, 1679 at Tyburn Tree in London:

John Gavan

William Harcourt

Anthony Turner

Thomas Whitbread

John Fenwick

Fathers John Fenwick and William Ireland were arrested in September of 1678 and held in prison. Then Oates captured Fathers Thomas Whitbread and Edward Mico, who were ill with the plague and living in the household of the Spanish ambassador. By December that year Father Whitbread was well enough to join Fathers Fenwick and Ireland in Newgate Prison; Father Mico died in custody. Father William Ireland was executed in January of 1679 with the Jesuit laybrother John Grove, but Fenwick and Whitbread awaited their fate and another trial. They had given evidence that refuted Oates', so Oates needed more time to gather more evidence! Fathers John Gavan, William Harcourt, and Anthony Turner in the meantime had been arrested and they were brought together with Father Fenwick and Whitbread (tried for the second time--no double jeopardy in Charles II's courts for Catholics!)

At the trial, the defense produced plenty of witnesses from Saint-Omer to testify that Oates hadn't even been in England the day he was supposed to have heard the Jesuits plotting to assassinate King Charles II--he was at the college in St. Omer's that day. But the Court told the jury to trust Oates' evidence over the Catholic witnesses. The jury returned a verdict of guilty, condemning the five Jesuits to die for treason.

The circumstances of their execution were quite dramatic. All five were standing in a cart under the scaffold, with their hands bound and the nooses around their necks. They had each spoken, each prepared themselves for death, when suddenly, a rider galloped up, crying "A Pardon, A Pardon!"

Charles II issued them a conditional pardon to spare their lives--all they had to was admit their guilt and tell him all they knew about the plot. Trouble was that they weren't guilty of any plot and they couldn't tell him what they knew because there wasn't any plot in the first place! They declined the pardon, protesting that they could not lie to save their lives--they could not risk their immortal souls to save their physical bodies.

Therefore, they prepared themselves again for death--the rider returned to Charles II with the news--the cart pulled away and they were hung until dead before their bodies were quartered and their heads cut off. They were buried in the churchyard of St. Giles in the Fields. According to the church's website, there are actually eleven of twelve martyrs originally buried there in the churchyard:

The testimony of Titus Oates, led during 1678-81, to the burial in St Giles Churchyard of twelve Roman Catholic martyrs who were later beatified - Whitebread, Harcourt, Fenwick, Gavan, Turner, Coleman, Langhorne, Mico, Ireland, Grove, Pickering and Oliver Plunket, Archbishop of Armagh. All were priests except Coleman, who was secretary to the Duchess of York, Langhorne, who was a barrister, Grove, and Pickering, who was a laybrother; and all except Mico, who died after his arrest, had been executed at Tyburn (then close to where Marble Arch now stands). The first five are the Jesuit fathers with whom Plunket asked to be buried in the churchyard of St. Giles. The burial place is said to be near the north wall of the church. Though the body of Oliver Plunket, who was canonised in 1975, was later exhumed and taken to Lamspringe in Germany (the head being now at Drogheda and the body at Downside), there is in the St. Giles Burial Register for 1 July, 1681 a most legible entry of the burial.

John Gavan

William Harcourt

Anthony Turner

Thomas Whitbread

John Fenwick

Fathers John Fenwick and William Ireland were arrested in September of 1678 and held in prison. Then Oates captured Fathers Thomas Whitbread and Edward Mico, who were ill with the plague and living in the household of the Spanish ambassador. By December that year Father Whitbread was well enough to join Fathers Fenwick and Ireland in Newgate Prison; Father Mico died in custody. Father William Ireland was executed in January of 1679 with the Jesuit laybrother John Grove, but Fenwick and Whitbread awaited their fate and another trial. They had given evidence that refuted Oates', so Oates needed more time to gather more evidence! Fathers John Gavan, William Harcourt, and Anthony Turner in the meantime had been arrested and they were brought together with Father Fenwick and Whitbread (tried for the second time--no double jeopardy in Charles II's courts for Catholics!)

At the trial, the defense produced plenty of witnesses from Saint-Omer to testify that Oates hadn't even been in England the day he was supposed to have heard the Jesuits plotting to assassinate King Charles II--he was at the college in St. Omer's that day. But the Court told the jury to trust Oates' evidence over the Catholic witnesses. The jury returned a verdict of guilty, condemning the five Jesuits to die for treason.

The circumstances of their execution were quite dramatic. All five were standing in a cart under the scaffold, with their hands bound and the nooses around their necks. They had each spoken, each prepared themselves for death, when suddenly, a rider galloped up, crying "A Pardon, A Pardon!"

Charles II issued them a conditional pardon to spare their lives--all they had to was admit their guilt and tell him all they knew about the plot. Trouble was that they weren't guilty of any plot and they couldn't tell him what they knew because there wasn't any plot in the first place! They declined the pardon, protesting that they could not lie to save their lives--they could not risk their immortal souls to save their physical bodies.

Therefore, they prepared themselves again for death--the rider returned to Charles II with the news--the cart pulled away and they were hung until dead before their bodies were quartered and their heads cut off. They were buried in the churchyard of St. Giles in the Fields. According to the church's website, there are actually eleven of twelve martyrs originally buried there in the churchyard:

The testimony of Titus Oates, led during 1678-81, to the burial in St Giles Churchyard of twelve Roman Catholic martyrs who were later beatified - Whitebread, Harcourt, Fenwick, Gavan, Turner, Coleman, Langhorne, Mico, Ireland, Grove, Pickering and Oliver Plunket, Archbishop of Armagh. All were priests except Coleman, who was secretary to the Duchess of York, Langhorne, who was a barrister, Grove, and Pickering, who was a laybrother; and all except Mico, who died after his arrest, had been executed at Tyburn (then close to where Marble Arch now stands). The first five are the Jesuit fathers with whom Plunket asked to be buried in the churchyard of St. Giles. The burial place is said to be near the north wall of the church. Though the body of Oliver Plunket, who was canonised in 1975, was later exhumed and taken to Lamspringe in Germany (the head being now at Drogheda and the body at Downside), there is in the St. Giles Burial Register for 1 July, 1681 a most legible entry of the burial.

Tuesday, June 19, 2012

Blessed Thomas Woodhouse: A Marian Priest

From the Catholic Encyclopedia: Blessed Thomas Woodhouse was a priest ordained during the reign of Mary I and a:

Martyr who suffered at Tyburn 19 June, 1573, being disembowelled alive. Ordained in Mary's reign, he was a Lincolnshire rector for under a year, and in 1560 acted as a private tutor in Wales. On 14 May, 1561, he was committed to the Fleet, London, having been arrested while saying Mass. For the rest of his life he remained in custody, uncompromising in his opposition to heresy, saying Mass in secret daily, reciting his Office regularly, and thirsting for martyrdom; but treated with considerable leniency till on 19 November, 1572, he sent the prison washerwoman to Lord Burghley's house with his famous letter. In it he begs him to seek reconciliation with the pope and earnestly to "persuade the Lady Elizabeth, who for her own great disobedience is most justly deposed, to submit herself unto her spiritual prince and father". Some days later in a personal interview he used equally definite language. Confined then by himself he wrote "divers papers, persuading men to the true faith and obedience", which he signed, tied to stones, and flung into the street. He was repeatedly examined both publicly and privately. Once, when he had denied the queen's title, someone said, "If you saw her Majesty, you would not say so, for her Majesty is great". "But the Majesty of God is greater", he answered. After being sentenced at the Guildhall either in April or on 16 June, he was taken to Newgate. He was admitted to the Society of Jesus in prison, though the Decree of the Congregation of Rites, 4 December, 1886, describes him as a secular priest. He is not to be confused with Thomas Wood.

He is the protomartyr of English Jesuits:

Thomas Woodhouse (1535-1573) was the first Jesuit to die in the conflict between pope and English crown, although he was only admitted to the Society just before his arrest. . . . At some point in 1572 he wrote the Jesuit provincial in Paris because the English mission was not yet established, and asked to become a member of the Society.

One note: Father Woodhouse was evidently an exception to the commonly accepted rule that Elizabeth's regime did not prosecute Catholic priests until after the Northern Rebellion and the Papal Bull of 1569 and 1570, for he was arrested and committed to prison for the rest of his life in 1561. Even a lenient prison sentence of 12 years is onerous, especially since his crime was saying Mass. Under the 1559 Act of Uniformity, he must have been caught saying Mass more than once--in fact, three times--if he was justly sentenced to life imprisonment under English law. He was really quite a pioneer, trying to figure out on his own what to do after his vocation as a Catholic priest had been effectively declared illegal.

Martyr who suffered at Tyburn 19 June, 1573, being disembowelled alive. Ordained in Mary's reign, he was a Lincolnshire rector for under a year, and in 1560 acted as a private tutor in Wales. On 14 May, 1561, he was committed to the Fleet, London, having been arrested while saying Mass. For the rest of his life he remained in custody, uncompromising in his opposition to heresy, saying Mass in secret daily, reciting his Office regularly, and thirsting for martyrdom; but treated with considerable leniency till on 19 November, 1572, he sent the prison washerwoman to Lord Burghley's house with his famous letter. In it he begs him to seek reconciliation with the pope and earnestly to "persuade the Lady Elizabeth, who for her own great disobedience is most justly deposed, to submit herself unto her spiritual prince and father". Some days later in a personal interview he used equally definite language. Confined then by himself he wrote "divers papers, persuading men to the true faith and obedience", which he signed, tied to stones, and flung into the street. He was repeatedly examined both publicly and privately. Once, when he had denied the queen's title, someone said, "If you saw her Majesty, you would not say so, for her Majesty is great". "But the Majesty of God is greater", he answered. After being sentenced at the Guildhall either in April or on 16 June, he was taken to Newgate. He was admitted to the Society of Jesus in prison, though the Decree of the Congregation of Rites, 4 December, 1886, describes him as a secular priest. He is not to be confused with Thomas Wood.

He is the protomartyr of English Jesuits:

Thomas Woodhouse (1535-1573) was the first Jesuit to die in the conflict between pope and English crown, although he was only admitted to the Society just before his arrest. . . . At some point in 1572 he wrote the Jesuit provincial in Paris because the English mission was not yet established, and asked to become a member of the Society.

One note: Father Woodhouse was evidently an exception to the commonly accepted rule that Elizabeth's regime did not prosecute Catholic priests until after the Northern Rebellion and the Papal Bull of 1569 and 1570, for he was arrested and committed to prison for the rest of his life in 1561. Even a lenient prison sentence of 12 years is onerous, especially since his crime was saying Mass. Under the 1559 Act of Uniformity, he must have been caught saying Mass more than once--in fact, three times--if he was justly sentenced to life imprisonment under English law. He was really quite a pioneer, trying to figure out on his own what to do after his vocation as a Catholic priest had been effectively declared illegal.

John Rogers Herbert and St. Thomas More

Thanks to this blog, I have discovered John Rogers Herbert of the Royal Academy, who depicted the famous episode of St. Thomas More standing at the window of his cell in the Tower of London on May 4, 1535 and seeing the five protomartyrs of the English Reformation led out to Tyburn and their brutal executions: