Just a quick note about St. Joan of Arc and the English Reformation--listening to the EWTN radio broadcast of Mass yesterday I heard the celebrant mention that if she had not led France in defeating the English during the Hundred Years War, at least of part of France (more than Calais!) might have been under English control. And that would have had consequences.

St. Joan was burned alive at the stake on May 30 in 1431. In 1531, one hundred years later, Henry VIII started his break away from the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church by forcing the Convocation of Bishops to acknowledge his authority over the Church in England "as far as God allows", and proclaiming himself the Supreme Head and Governor of the Ecclesiae Anglicanae in the Act of Supremacy three years later. Thus if she had not helped rally France to defeat the English, "France" would have participated in the English Reformation, her great monasteries suppressed (250 years before the French Revolution's suppression), statues and paintings of Notre Dame crushed and burned along with other great Christian art, and many glorious Gothic cathedrals despoiled and destroyed, their shrines and relics, treasures and art plundered--Chartres without the Sancta Camisa, Sainte Chapelle without the relic of the Crown of Thorns--again anticipating much of the iconoclasm that did occur after the French Revolution. But without St. Joan of Arc, hearing the voices of the saints, going to her country's weak king, and leading France to victory, France would have been Anglican (Protestant) in the 16th century, and western culture, Catholic culture, would have lost the same things in France as were lost in England: art, music, visual beauty, books, monasticism, and worship.

This website suggests other aspects of an alternative history without St. Joan of Arc:

What events might not have happened without Joan of Arc saving France? Without Joan of Arc it is very doubtful that France would have become the strong unified nation that it became. Without a strong France many of the later events that occurred in Europe and around the world would have been much different. It is even conceivable that American independence from Britain would never have happened because it was the French military assistance that made the difference and directly caused the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

Do you think France would've existed to this day without Joan of Arc's actions? Joan helped to give the people of France a national identity. Before Joan people would identify themselves as being from parts of France such as people from the region of Burgundy calling themselves Burgundians. After Joan of Arc the people were much more likely to identify themselves as being French. It was having a national identity that helped forge the great nation that France became and still is today.

In one of those strange ironies, the Church of England honors Joan of Arc on their liturgical calendar--as a visionary (not necessarily because her visions were true, but because she listened to them)! The Catholic Church honors St. Joan of Arc as a martyr and virgin, unjustly condemned to death; a holy Maiden who loved Jesus and Notre Dame.

Further research and information on the English Reformation, English Catholic martyrs, and related topics by the author of SUPREMACY AND SURVIVAL: HOW CATHOLICS ENDURED THE ENGLISH REFORMATION

Saturday, May 31, 2014

Friday, May 30, 2014

Newman Oratories and the Liturgical Life in England

I have experienced Mass at the London (Brompton) and the Oxford Oratories--I must get to Mass at the Birmingham Oratory: it's on my bucket list! This article, which I found while searching for something else, has some great details about "The Contribution of the Oratories to the Liturgical Life of England" and I commend it to your reading.

Among the interesting notes: Newman did not agree with A.W.N. Pugin that the Gothic was THE only style of architecture appropriate for Catholic churches. Indeed, Newman thought that the Classical style was more appropriate because of its "simplicity, purity, elegance, beauty, [and] brightness". Father Nicholls states that, "He believed that the most suitable model for a Catholic Church in England after the emancipation was not to be found in the Gothic revival, but in the great Churches of the Roman Baroque, where the Altar was close to the congregation, and easily visible; where the tabernacle was prominent and the Blessed Sacrament was the focus of attention throughout the building."

Father Nicholls also addresses the contributions two Oratorians made to liturgical music by Edward Caswall and Frederick Faber; classical music at the Birmingham Oratory (Newman favored the Viennese masters like Mozart, Haydn, Cherubini, Hummel, and Beethoven over plainchant and polyphony!); the subsequent development of plainchant and polyphony after Pope St. Pius X issued his Motu Proprio on liturgical music in 1903; the use of Latin in Oratory Masses; the traditions of celebrating High Mass and Sunday Vespers, and the practice of the celebrant facing the Altar during Mass.

Very enlightening. Read the rest here.

Among the interesting notes: Newman did not agree with A.W.N. Pugin that the Gothic was THE only style of architecture appropriate for Catholic churches. Indeed, Newman thought that the Classical style was more appropriate because of its "simplicity, purity, elegance, beauty, [and] brightness". Father Nicholls states that, "He believed that the most suitable model for a Catholic Church in England after the emancipation was not to be found in the Gothic revival, but in the great Churches of the Roman Baroque, where the Altar was close to the congregation, and easily visible; where the tabernacle was prominent and the Blessed Sacrament was the focus of attention throughout the building."

Father Nicholls also addresses the contributions two Oratorians made to liturgical music by Edward Caswall and Frederick Faber; classical music at the Birmingham Oratory (Newman favored the Viennese masters like Mozart, Haydn, Cherubini, Hummel, and Beethoven over plainchant and polyphony!); the subsequent development of plainchant and polyphony after Pope St. Pius X issued his Motu Proprio on liturgical music in 1903; the use of Latin in Oratory Masses; the traditions of celebrating High Mass and Sunday Vespers, and the practice of the celebrant facing the Altar during Mass.

Very enlightening. Read the rest here.

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Happy Birthday to Gilbert Keith Chesterton!

As our Wichita chapter of the American Chesterton Society continues to read Chesterton, we've appreciated how he looks at historical events from a different perspective. This short article from Lunacy and Letters, posted on the American Chesterton Society's website, shows why Chesterton offers those different views--he does not want to read what the historian thinks about history; he just wants to read history:

In my innocent and ardent youth I had a fixed fancy. I held that children in a school ought to be taught history, and ought to be taught nothing else. The story of human society is the only fundamental framework outside of religion in which everything can fall into its place. A boy cannot see the importance of Latin simply by learning Latin. But he might see it by learning the history of the Latins. Nobody can possibly see any sense in learning geography or in learning arithmetic – both studies are obviously nonsense. But on the eager eve of Austerlitz, where Napoleon was fighting a superior force in a foreign country, one might see the need for Napoleon knowing a little geography and a little arithmetic. I have thought that if people would only learn history, they would learn to learn everything else. Algebra might seem ugly, yet the very name of it is connected with something so romantic as the Crusades, for the word is from the Saracens. Greek might be ugly until one knew the Greeks, but surely not afterwards. History is simply humanity. And history will humanise all studies, even anthropology.

Since that age of innocence I have, however, realised that there is a difficulty in this teaching of history. And the difficulty is that there is no history to teach. This is not a scrap of cynicism – it is a genuine and necessary product of the many points of view and the strong mental separations of our society, for in our age every man has a cosmos of his own, and is therefore horribly alone. There is no history; there are only historians. To tell the tale plainly is now much more difficult than to tell it treacherously. It is unnatural to leave the facts alone; it is instinctive to pervert them. The very words involved in the chronicles – “Pagan”, “Puritan”, “Catholic”, “Republican”, “Imperialist” – are words which make us leap out of our armchairs.

No good modern historians are impartial. All modern historians are divided into two classes – those who tell half the truth, like Macaulay and Froude, and those who tell none of the truth, like Hallam and the Impartials. The angry historians see one side of the question. The calm historians see nothing at all, not even the question itself.

But there is another possible attitude towards the records of the past, and I have never been able to understand why it has not been more often adopted. To put it in its curtest form, my proposal is this: That we should not read historians, but history. Let us read the actual text of the times. Let us, for a year, or a month, or a fortnight, refuse to read anything about Oliver Cromwell except what was written while he was alive. There is plenty of material; from my own memory (which is all I have to rely on in the place where I write) I could mention offhand many long and famous efforts of English literature that cover the period. Clarendon’s History, Evelyn’s Diary, the Life of Colonel Hutchinson. Above all let us read all Cromwell’s own letters and speeches, as Carlyle published them. But before we read them let us carefully paste pieces of stamp-paper over every sentence written by Carlyle. Let us blot out in every memoir every critical note and every modern paragraph. For a time let us cease altogether to read the living men on their dead topics. Let us read only the dead men on their living topics.

In my innocent and ardent youth I had a fixed fancy. I held that children in a school ought to be taught history, and ought to be taught nothing else. The story of human society is the only fundamental framework outside of religion in which everything can fall into its place. A boy cannot see the importance of Latin simply by learning Latin. But he might see it by learning the history of the Latins. Nobody can possibly see any sense in learning geography or in learning arithmetic – both studies are obviously nonsense. But on the eager eve of Austerlitz, where Napoleon was fighting a superior force in a foreign country, one might see the need for Napoleon knowing a little geography and a little arithmetic. I have thought that if people would only learn history, they would learn to learn everything else. Algebra might seem ugly, yet the very name of it is connected with something so romantic as the Crusades, for the word is from the Saracens. Greek might be ugly until one knew the Greeks, but surely not afterwards. History is simply humanity. And history will humanise all studies, even anthropology.

Since that age of innocence I have, however, realised that there is a difficulty in this teaching of history. And the difficulty is that there is no history to teach. This is not a scrap of cynicism – it is a genuine and necessary product of the many points of view and the strong mental separations of our society, for in our age every man has a cosmos of his own, and is therefore horribly alone. There is no history; there are only historians. To tell the tale plainly is now much more difficult than to tell it treacherously. It is unnatural to leave the facts alone; it is instinctive to pervert them. The very words involved in the chronicles – “Pagan”, “Puritan”, “Catholic”, “Republican”, “Imperialist” – are words which make us leap out of our armchairs.

No good modern historians are impartial. All modern historians are divided into two classes – those who tell half the truth, like Macaulay and Froude, and those who tell none of the truth, like Hallam and the Impartials. The angry historians see one side of the question. The calm historians see nothing at all, not even the question itself.

But there is another possible attitude towards the records of the past, and I have never been able to understand why it has not been more often adopted. To put it in its curtest form, my proposal is this: That we should not read historians, but history. Let us read the actual text of the times. Let us, for a year, or a month, or a fortnight, refuse to read anything about Oliver Cromwell except what was written while he was alive. There is plenty of material; from my own memory (which is all I have to rely on in the place where I write) I could mention offhand many long and famous efforts of English literature that cover the period. Clarendon’s History, Evelyn’s Diary, the Life of Colonel Hutchinson. Above all let us read all Cromwell’s own letters and speeches, as Carlyle published them. But before we read them let us carefully paste pieces of stamp-paper over every sentence written by Carlyle. Let us blot out in every memoir every critical note and every modern paragraph. For a time let us cease altogether to read the living men on their dead topics. Let us read only the dead men on their living topics.

Read the rest here. Happy birthday, G.K.C.! (May 29, 1874).

Tolkien's Beowulf

J.R.R. Tolkien's son Christopher has edited his father's translation and notes about the great poem Beowulf. Craig Williamson reviews it for The Wall Street Journal:

Over a thousand years before Bilbo Baggins crept into Smaug's lair to lift a cup from the dragon's hoard, a nameless slave came slinking into the dragon's cave in "Beowulf" to steal a cup that led to the worm's fiery retaliation. Long before Frodo Baggins battled the forces of evil in Gollum, Shelob and Sauron, Beowulf did battle with the monster Grendel, his mother and the dragon. Before there was Tolkien's Middle-earth, there was the Old English middangeard (literally, "middle-yard, middle-world"), a place where history and fantasy met, where heroes did battle with both their real enemies and the creatures of their collective imagination.

Now at last we have Tolkien's version of the poem, as well as several other important texts related to it. First and foremost is his prose translation, which he completed in 1926 at the age of 34 and revised over the years and which his son Christopher, who edited this volume, characterizes as "in one sense complete, but at the same time evidently 'unfinished.' " There is also a generous selection of lecture notes and commentary on the Old English text, geared to Tolkien's translation. This is followed by three versions, one in Old English, two in modern English, of a short story, "Sellic Spell" (a phrase from "Beowulf" that means "marvelous story"), and two versions of a short ballad by Tolkien called "The Lay of Beowulf."

Williamson discusses briefly the "ethics" of publishing these works that Tolkien had not prepared himself for publication:

The ethics of publishing an author's unfinished works are admittedly complex, but Christopher Tolkien has argued that his father's drafts, works in progress and commentaries are important to our understanding of his work. Both scholars and lay readers have long awaited Tolkien's "Beowulf" translation and its related materials, and everyone will find something of enduring interest in this collection. For Tolkien, "Beowulf" was both a brilliant and haunting work in its own right and an inspiration for his own fiction. It is a poem that will move us as readers, not forever but as long as we last. Or as Tolkien says, "It must ever call with a profound appeal—until the dragon comes."

The HarperCollins site announcing the publication has further comments by Christopher Tolkien:

The translation of Beowulf by J.R.R. Tolkien was an early work, very distinctive in its mode, completed in 1926: he returned to it later to make hasty corrections, but seems never to have considered its publication. This edition is twofold, for there exists an illuminating commentary on the text of the poem by the translator himself, in the written form of a series of lectures given at Oxford in the 1930s; and from these lectures a substantial selection has been made, to form also a commentary on the translation in this book.

From his creative attention to detail in these lectures there arises a sense of the immediacy and clarity of his vision. It is as if he entered into the imagined past: standing beside Beowulf and his men shaking out their mail-shirts as they beached their ship on the coast of Denmark, listening to the rising anger of Beowulf at the taunting of Unferth, or looking up in amazement at Grendel’s terrible hand set under the roof of Heorot.

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Blessed Margaret Pole in "The Tablet"

In 1941, The Tablet published this article about Blessed Margaret Pole, executed on May 28, 1541, four hundred years before:

The sixteenth century seems to hive been the era in excelsis of the English Matriarch, and we see her no less in the fiery Bess of Hardwick and the sweet Anne Dacres and a host of supernumeraries than in the widely divergent characters of Mary and Elizabeth. Certainly we have her at her best in the dogged and noble character of the Blessed Countess of Salisbury, who was "prepared to swear by her damnation when it was necessary to enforce a serious point." She has frequently been compared with the Mother of the Machabees, and the parallel is a close one. She saw the physical or mental suffering of many of her children and crowned her endurance with a bloody martyrdom.

This week brings us to the fourth centenary of the execution of this courageous woman. As one of the Henrician martyrs she stands in the same category as the Blessed Carthusians and S. John Fisher and S. Thomas More. By 1541 it seemed that nothing could stem the ruthless drive against those who stood loyal to the Apostolic See ; and she who in his better days had been praised by Henry for her exalted virtues was now abandoned by him in the depth of his depravity to a death so ignominious that the contemporary ambassadorial despatches are eloquent with righteous indignation. . . .

The greatest offence of Blessed Margaret was that she was the mother of the Cardinal, and for that reason she met her death. In November 1538, ten days after the apprehension of two of her sons, Lord Montague of Buckmere and Sir Geoffrey Pole, and others of her kindred who Were executed, the Venerable Countess was herself arrested. Bishop Goodrich of Ely and Admiral Fitzwilliam, later Earl of Southampton and a cousin of Anne Boleyn, were sent to examine her at her own house at Warblington in Hampshire, which was searched from cellar to attic. She had there a considerable establishment, with three chaplains in residence. A few undated Papal Bulls were found on the premises. Her neighbours and tenants were closely questioned, and it was alleged that she had forbidden the latter to read the Bible in English. However, the inquisitors reported to Cromwell that although they had "travailed with her" for many hours she would "nothing utter," and they were forced to conclude that either her sons had left her out of their "treacherous" counsels or else that she was "the most arrant traitress that ever lived." For some time she was a prisoner at Cowdray Park, Sussex, where she suffered many indignities and was constantly invigilated by the Admiral. Finally, she was sent to the Tower which she never again left, and despite her seventy summers managed to endure two years of deprivation in which lack of clothing and nourishment were her chief trials. It was quite suddenly that she was led out to execution, on May 28th, 1541. A splendid Torrigiano tomb had been prepared to receive her mortal remains at Christ Church, but they were not suffered to be placed there and the tomb itself was ruthlessly defaced by Cromwell's own orders.

Beccadelli, later Archbishop of Ragusa and the Boswell of the Cardinal wrote as follows : "I was with Cardinal Pole when he heard of his Mother's death. To me he said 'Hitherto I thought God had given me the grace to be the son of the best and most honourable lady in England, and I gloried in the fact and thanked God for it. Now however he has honoured me still more, and increased my debt of gratitude to Him, for He has made me the son of a Martyr. For her constancy in the Catholic Faith the King has caused her to be publicly beheaded, in spite of her seventy years. Blessed and thanked be God for ever!'

As we often look upon the martyrs as inspiration for how to live and how to die for Jesus and His Church, these lessons, from an article by Celine McCoy on the Catholic Exchange, seem most apt for remembering and modeling Blessed Margaret Pole:

1. Every one of us hopes to die peacefully in our beds, and what else should a 70-year-old widow have expected? She had been a faithful wife, mother, and governess to a princess, loyal to her king in all things except for his unlawful marriage to Anne Boleyn. Perhaps she could have saved her life by keeping quiet or by denying her son’s position against the king. But Margaret remained faithful to her true King; while she suffered on earth, we know that she has been rewarded according to His promise: “Everyone who has left houses, brothers, sisters, father, mother, children, or land for the sake of my name will be repaid a hundred times over, and also inherit eternal life” (Matthew 19:29).

2. Today our lives may not be on the line for our beliefs, but are there opportunities to speak the truth that we are avoiding because we don’t want to lose friends, the respect of our co-workers, or because we fear possible derision? Let us pray to Blessed Margaret to help us calmly and fearlessly stand up for the truth, no matter the cost to ourselves.

Blessed Margaret Pole, pray for us!

The sixteenth century seems to hive been the era in excelsis of the English Matriarch, and we see her no less in the fiery Bess of Hardwick and the sweet Anne Dacres and a host of supernumeraries than in the widely divergent characters of Mary and Elizabeth. Certainly we have her at her best in the dogged and noble character of the Blessed Countess of Salisbury, who was "prepared to swear by her damnation when it was necessary to enforce a serious point." She has frequently been compared with the Mother of the Machabees, and the parallel is a close one. She saw the physical or mental suffering of many of her children and crowned her endurance with a bloody martyrdom.

This week brings us to the fourth centenary of the execution of this courageous woman. As one of the Henrician martyrs she stands in the same category as the Blessed Carthusians and S. John Fisher and S. Thomas More. By 1541 it seemed that nothing could stem the ruthless drive against those who stood loyal to the Apostolic See ; and she who in his better days had been praised by Henry for her exalted virtues was now abandoned by him in the depth of his depravity to a death so ignominious that the contemporary ambassadorial despatches are eloquent with righteous indignation. . . .

The greatest offence of Blessed Margaret was that she was the mother of the Cardinal, and for that reason she met her death. In November 1538, ten days after the apprehension of two of her sons, Lord Montague of Buckmere and Sir Geoffrey Pole, and others of her kindred who Were executed, the Venerable Countess was herself arrested. Bishop Goodrich of Ely and Admiral Fitzwilliam, later Earl of Southampton and a cousin of Anne Boleyn, were sent to examine her at her own house at Warblington in Hampshire, which was searched from cellar to attic. She had there a considerable establishment, with three chaplains in residence. A few undated Papal Bulls were found on the premises. Her neighbours and tenants were closely questioned, and it was alleged that she had forbidden the latter to read the Bible in English. However, the inquisitors reported to Cromwell that although they had "travailed with her" for many hours she would "nothing utter," and they were forced to conclude that either her sons had left her out of their "treacherous" counsels or else that she was "the most arrant traitress that ever lived." For some time she was a prisoner at Cowdray Park, Sussex, where she suffered many indignities and was constantly invigilated by the Admiral. Finally, she was sent to the Tower which she never again left, and despite her seventy summers managed to endure two years of deprivation in which lack of clothing and nourishment were her chief trials. It was quite suddenly that she was led out to execution, on May 28th, 1541. A splendid Torrigiano tomb had been prepared to receive her mortal remains at Christ Church, but they were not suffered to be placed there and the tomb itself was ruthlessly defaced by Cromwell's own orders.

Beccadelli, later Archbishop of Ragusa and the Boswell of the Cardinal wrote as follows : "I was with Cardinal Pole when he heard of his Mother's death. To me he said 'Hitherto I thought God had given me the grace to be the son of the best and most honourable lady in England, and I gloried in the fact and thanked God for it. Now however he has honoured me still more, and increased my debt of gratitude to Him, for He has made me the son of a Martyr. For her constancy in the Catholic Faith the King has caused her to be publicly beheaded, in spite of her seventy years. Blessed and thanked be God for ever!'

As we often look upon the martyrs as inspiration for how to live and how to die for Jesus and His Church, these lessons, from an article by Celine McCoy on the Catholic Exchange, seem most apt for remembering and modeling Blessed Margaret Pole:

1. Every one of us hopes to die peacefully in our beds, and what else should a 70-year-old widow have expected? She had been a faithful wife, mother, and governess to a princess, loyal to her king in all things except for his unlawful marriage to Anne Boleyn. Perhaps she could have saved her life by keeping quiet or by denying her son’s position against the king. But Margaret remained faithful to her true King; while she suffered on earth, we know that she has been rewarded according to His promise: “Everyone who has left houses, brothers, sisters, father, mother, children, or land for the sake of my name will be repaid a hundred times over, and also inherit eternal life” (Matthew 19:29).

2. Today our lives may not be on the line for our beliefs, but are there opportunities to speak the truth that we are avoiding because we don’t want to lose friends, the respect of our co-workers, or because we fear possible derision? Let us pray to Blessed Margaret to help us calmly and fearlessly stand up for the truth, no matter the cost to ourselves.

Blessed Margaret Pole, pray for us!

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

Dominic Selwood on the English Reformation

Writing on his Telegraph blog about how history can be manipulated by the ruling party, Dominic Selwood writes:

So what about England? Has our constitutional monarchy and ancient tradition of parliamentary democracy protected our history from political manipulation? Can we rely on what we are taught and told, or are there myths we, too, have swallowed hook, line, and sinker?

Where better to start than with that most quintessentially English of events — the break with Rome that signalled the birth of modern England?

For centuries, the English have been taught that the late medieval Church was superstitious, corrupt, exploitative, and alien. Above all, we were told that King Henry VIII and the people of England despised its popish flummery and primitive rites. England was fed up to the back teeth with the ignorant mumbo-jumbo magicians of the foreign Church, and up and down the country Tudor people preferred plain-speaking, rational men like Wycliffe, Luther, and Calvin. Henry VIII achieved what all sane English and Welsh people had long desired – an excuse to break away from an anachronistic subjugation to the ridiculous medieval strictures of the Church.

For many in England, the subject of whether or not this was true was not even up for debate. Even now, the historical English disdain for all things Catholic is often regarded as irrefutable and objective fact. Otherwise why would we have been taught it for four and a half centuries? And anyway, the English are quite clearly not an emotional race like some of our continental cousins. We like our churches bright and clean and practical and full of common sense. For this reason, we are brought up to believe that Catholicism is just fundamentally, well … un-English.

But the last 30 years have seen a revolution in Reformation research. Leading scholars have started looking behind the pronouncements of the religious revolution’s leaders – Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley – and beyond the parliamentary pronouncements and the great sermons. Instead, they have begun focusing on the records left by ordinary English people. This “bottom up” approach to history has undoubtedly been the most exciting development in historical research in the last 50 years. It has taken us away from what the rulers want us to know, and steered us closer towards what actually happened.

But the last 30 years have seen a revolution in Reformation research. Leading scholars have started looking behind the pronouncements of the religious revolution’s leaders – Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley – and beyond the parliamentary pronouncements and the great sermons. Instead, they have begun focusing on the records left by ordinary English people. This “bottom up” approach to history has undoubtedly been the most exciting development in historical research in the last 50 years. It has taken us away from what the rulers want us to know, and steered us closer towards what actually happened.

Golly, you'd almost think he'd read my book!

I thought this was a particularly well-reasoned analysis of the violence of Henry VIII's imposition of his break from Rome:

The Tudor violence meted out to enforce the break with Rome was extreme, designed to deter by shock. For instance, one of Henry’s earliest victims was Sister Elizabeth Barton, a Benedictine nun. When she criticised Henry’s desire to marry Anne Boleyn, he had her executed, and her head spiked on London Bridge — the first and only woman ever to have suffered this posthumous barbarity.

Henry and his inner circle of politicians and radical clerics put to death hundreds of dissenters, pour encourager les autres. None of these people were plotting to kill him or destabilise his rule. Their “treason” was to oppose the destruction of their religion or the despoiling of their property. The brutal strangulation, emasculation, disembowelling, beheading, and quartering they endured as traitors was hideous, as was the total absence of any form of due process or justice.

Henry's use of attainder, meaning that the accused was never tried nor really even knew the charges against them, was brought up in an article by Suzannah Lipscomb in History Today, discussing whether or not Henry VIII was a tyrant:

Yet one of these laws, passed in 1539, ordered that royal proclamations would henceforth have the same status in law as statute. In other words, Henry used Parliament to eradicate the need for it and to make his word – quite literally – law. Similarly he condemned to death, through Parliament, an unprecedented number of people who were available for trial by the use of acts of attainder – acts of Parliament by which the accused was declared guilty and his property and life forfeited without trial or the need to cite precise evidence or name specific crimes. This is how Henry’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, and first minister, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, were dispatched.

Blessed Margaret Pole, Blessed Adrian Fortescue, and Blessed Thomas Dingley were also all executed under a Bill of Attainder. They were not plotting to bring down Henry VIII's rule--but all three were wealthy Catholics. Henry was able to seize the treasure of the Knights of Jerusalem and the lands of Countess of Salisbury by bringing them to the block, making up conspiracies out of travels to the Continent and devotion to the Five Wounds of Christ.

But I think Selwood is wrong to ignore the fact that those burned at the stake during the reign of Mary I were not plotting to kill her or "destabilize" her rule either. Cranmer, of course, had been found guilty of treason against the rightful heir, and could have been beheaded. Certainly, the Catholic martyrs of the Elizabethan era who have been beatified and canonized were not plotting against Elizabeth.

Otherwise, Selwood provides an interesting and spirited summary of the revisionist history more or less accepted now about the English Reformation.

So what about England? Has our constitutional monarchy and ancient tradition of parliamentary democracy protected our history from political manipulation? Can we rely on what we are taught and told, or are there myths we, too, have swallowed hook, line, and sinker?

Where better to start than with that most quintessentially English of events — the break with Rome that signalled the birth of modern England?

For centuries, the English have been taught that the late medieval Church was superstitious, corrupt, exploitative, and alien. Above all, we were told that King Henry VIII and the people of England despised its popish flummery and primitive rites. England was fed up to the back teeth with the ignorant mumbo-jumbo magicians of the foreign Church, and up and down the country Tudor people preferred plain-speaking, rational men like Wycliffe, Luther, and Calvin. Henry VIII achieved what all sane English and Welsh people had long desired – an excuse to break away from an anachronistic subjugation to the ridiculous medieval strictures of the Church.

For many in England, the subject of whether or not this was true was not even up for debate. Even now, the historical English disdain for all things Catholic is often regarded as irrefutable and objective fact. Otherwise why would we have been taught it for four and a half centuries? And anyway, the English are quite clearly not an emotional race like some of our continental cousins. We like our churches bright and clean and practical and full of common sense. For this reason, we are brought up to believe that Catholicism is just fundamentally, well … un-English.

But the last 30 years have seen a revolution in Reformation research. Leading scholars have started looking behind the pronouncements of the religious revolution’s leaders – Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley – and beyond the parliamentary pronouncements and the great sermons. Instead, they have begun focusing on the records left by ordinary English people. This “bottom up” approach to history has undoubtedly been the most exciting development in historical research in the last 50 years. It has taken us away from what the rulers want us to know, and steered us closer towards what actually happened.

But the last 30 years have seen a revolution in Reformation research. Leading scholars have started looking behind the pronouncements of the religious revolution’s leaders – Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley – and beyond the parliamentary pronouncements and the great sermons. Instead, they have begun focusing on the records left by ordinary English people. This “bottom up” approach to history has undoubtedly been the most exciting development in historical research in the last 50 years. It has taken us away from what the rulers want us to know, and steered us closer towards what actually happened.Golly, you'd almost think he'd read my book!

I thought this was a particularly well-reasoned analysis of the violence of Henry VIII's imposition of his break from Rome:

The Tudor violence meted out to enforce the break with Rome was extreme, designed to deter by shock. For instance, one of Henry’s earliest victims was Sister Elizabeth Barton, a Benedictine nun. When she criticised Henry’s desire to marry Anne Boleyn, he had her executed, and her head spiked on London Bridge — the first and only woman ever to have suffered this posthumous barbarity.

Henry and his inner circle of politicians and radical clerics put to death hundreds of dissenters, pour encourager les autres. None of these people were plotting to kill him or destabilise his rule. Their “treason” was to oppose the destruction of their religion or the despoiling of their property. The brutal strangulation, emasculation, disembowelling, beheading, and quartering they endured as traitors was hideous, as was the total absence of any form of due process or justice.

Henry's use of attainder, meaning that the accused was never tried nor really even knew the charges against them, was brought up in an article by Suzannah Lipscomb in History Today, discussing whether or not Henry VIII was a tyrant:

Yet one of these laws, passed in 1539, ordered that royal proclamations would henceforth have the same status in law as statute. In other words, Henry used Parliament to eradicate the need for it and to make his word – quite literally – law. Similarly he condemned to death, through Parliament, an unprecedented number of people who were available for trial by the use of acts of attainder – acts of Parliament by which the accused was declared guilty and his property and life forfeited without trial or the need to cite precise evidence or name specific crimes. This is how Henry’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, and first minister, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex, were dispatched.

Blessed Margaret Pole, Blessed Adrian Fortescue, and Blessed Thomas Dingley were also all executed under a Bill of Attainder. They were not plotting to bring down Henry VIII's rule--but all three were wealthy Catholics. Henry was able to seize the treasure of the Knights of Jerusalem and the lands of Countess of Salisbury by bringing them to the block, making up conspiracies out of travels to the Continent and devotion to the Five Wounds of Christ.

But I think Selwood is wrong to ignore the fact that those burned at the stake during the reign of Mary I were not plotting to kill her or "destabilize" her rule either. Cranmer, of course, had been found guilty of treason against the rightful heir, and could have been beheaded. Certainly, the Catholic martyrs of the Elizabethan era who have been beatified and canonized were not plotting against Elizabeth.

Otherwise, Selwood provides an interesting and spirited summary of the revisionist history more or less accepted now about the English Reformation.

Monday, May 26, 2014

Tolkien and Lewis at Eighth Day Books

My husband and I enjoyed celebrating one of Eighth Day Books' two anniversaries Saturday night (the May anniversary is of its moving to its present location at 2838 East Douglas; the September anniversary is of its opening; last year was its 25th anniversary!). I baked a carrot cake and Warren's wife Chris had prepared a nice selection of snacks--a group of our friends met and we sat and talked about books, and education, and faith, and family for about three hours.

My husband and I enjoyed celebrating one of Eighth Day Books' two anniversaries Saturday night (the May anniversary is of its moving to its present location at 2838 East Douglas; the September anniversary is of its opening; last year was its 25th anniversary!). I baked a carrot cake and Warren's wife Chris had prepared a nice selection of snacks--a group of our friends met and we sat and talked about books, and education, and faith, and family for about three hours.

But now, to my purchases that evening: The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary from OUP and Medieval Literary: A Compendium of Medieval Knowledge with the Guidance of C.S. Lewis from Fons Vitae! When Warren showed me the latter I immediately thought of C.S. Lewis' The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, which I own in the old Cambridge University Press paperback, and which is filled with notes taken on mimeographed pages, recycled from the WSU History Department! I also bought two beautiful cards from the Laughing Elephant press, with illustrations by Marie Angel and quotations by Fyodor Dostoevsky and Jakob Bohme, like this one:

Only at Eighth Day Books, I think, could one find such a combination of erudition and beauty, friendship and delight, wine and cheese, snacks and cake, memories and future hopes--we are planning a reunion of our Ignatius J. Reilly reading group there in a few months--so many of the joys of life. Speaking of memories, one of my most cherished memories of Eighth Day Books was the night we all gathered for my book reading and signing! Here's a picture of my late father and my sister. Thinking of him this Memorial Day, I recall how proud he was of me that night, how much he enjoyed the festivity, and of course, how much I and all my family miss him!

Sunday, May 25, 2014

Samuel Webbe and English Catholics in the Eighteenth Century

I mentioned Samuel Webbe in my post last Sunday about the Mass at Our Lady and St. Gregory, Warwick Street to honor the Portuguese ambassador. He died on May 29 in 1816--25 years after the Catholic Relief Act of 1791 and 13 years before Catholic Emancipation. The Friends of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham highlights him on their Music tab:

English composer, born in England in 1742; died in London, 29 May, 1816. He studied under Barbaudt. In 1766 he was given a prize medal by the Catch Club for his O that I had wings, and in all he obtained twenty-seven medals for as many canons, catches, and glees, including Discord, dire sister, Glory be to the Father, Swiftly from the mountain’s brow, and To thee all angels. Other glees like When winds breathe soft, Thy voice, O Harmony, and Would you know my Celia’s charms are even better known. In 1776 he succeeded George Paxton as organist of the chapel of the Sardinian embassy, a position which he held until 1795: he was also organist of the Portuguese chapel. His Collection of Motetts (1792) and A Collection of Masses for Small Choirs were extensively used in Catholic churches throughout Great Britain from 1795 to the middle of the last century. If not of a very high order, they are at least devotional, and some are still sung. He also published nine books of glees, between the years 1764 and 1798, and some songs. His glees are his best claim on posterity.

Roman Catholic church music in England served the needs of a vigorous, vibrant and multi-faceted community that grew from about 70,000 to 1.7 million people during the long nineteenth century. Contemporary literature of all kinds abounds, along with numerous collections of sheet music, some running to hundreds, occasionally even thousands, of separate pieces, many of which have since been forgotten. Apart from compositions in the latest Classical Viennese styles and their successors, much of the music performed constituted a revival or imitation of older musical genres, especially plainchant and Renaissance Polyphony. Furthermore, many pieces that had originally been intended to be performed by professional musicians for the benefit of privileged royal, aristocratic or high ecclesiastical elites were repackaged for rendition by amateurs before largely working or lower middle class congregations, many of them Irish.

However, outside Catholic circles, little attention has been paid to this subject. Consequently, the achievements and widespread popularity of many composers (such as Joseph Egbert Turner, Henry George Nixon or John Richardson) within the English Catholic community have passed largely unnoticed. Worse still, much of the evidence is rapidly disappearing, partly because it no longer seems relevant to the needs of the modern Catholic Church in England.

This book provides a framework of the main aspects of Catholic church music in this period, showing how and why it developed in the way it did. Dr Muir sets the music in its historical, liturgical and legal context, pointing to the ways in which the music itself can be used as evidence to throw light on the changing character of English Catholicism. As a result the book will appeal not only to scholars and students working in the field, but also to church musicians, liturgists, historians, ecclesiastics and other interested Catholic and non-Catholic parties.

English composer, born in England in 1742; died in London, 29 May, 1816. He studied under Barbaudt. In 1766 he was given a prize medal by the Catch Club for his O that I had wings, and in all he obtained twenty-seven medals for as many canons, catches, and glees, including Discord, dire sister, Glory be to the Father, Swiftly from the mountain’s brow, and To thee all angels. Other glees like When winds breathe soft, Thy voice, O Harmony, and Would you know my Celia’s charms are even better known. In 1776 he succeeded George Paxton as organist of the chapel of the Sardinian embassy, a position which he held until 1795: he was also organist of the Portuguese chapel. His Collection of Motetts (1792) and A Collection of Masses for Small Choirs were extensively used in Catholic churches throughout Great Britain from 1795 to the middle of the last century. If not of a very high order, they are at least devotional, and some are still sung. He also published nine books of glees, between the years 1764 and 1798, and some songs. His glees are his best claim on posterity.

Lest you are confused, Webbe did not write for the TV show Glee; he wrote English a cappella part songs, scored for three to four voices, although Glee clubs did sing them:

Discord!Dire sister of the slaughtering power,

Small at her

birth, but rising every hour,

While scarce

the skies her horrid head can bound,

She stalks

on earth, and shakes the world around.

But lovely

Peace in angel form

Descending

quells the rising storm.

Soft ease

and sweet content shall reign

And Discord

never rise again.

The same site that highlighted Webbe notes that "The penal laws and the persecution of Catholics during the 220 years from 1558

to 1778 prevented any development of music by and for Catholics."

This intrigues me. William Byrd's great output of liturgical music for all the propers of the Roman Missal dates from the 17th century, and I know that composers like Peter Phillips fled to the Continent to both practice their faith and compose music. Since Catholics were only able to attend Mass secretly in hidden chapels in recusant safe houses, Low Mass, silent and somber, was the rule. According to this presentation by an Oratorian priest, there was little congregational singing, and even when rarely celebrated, Benediction was accompanied by recitation of the great Eucharistic hymns of St. Thomas Aquinas. In the Embassy chapels, the liturgical music, if it represented more modern compositions than Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony, was by German, Italian, Portuguese, or Spanish composers, so English Catholics attending those Masses heard international music, not by their own.

Ashgate publishes Roman Catholic Church Music in England, 1791–1914: A Handmaid of the Liturgy? by T.E. Muir that addresses developments after the 1791 Catholic Relief Act until World War I:

However, outside Catholic circles, little attention has been paid to this subject. Consequently, the achievements and widespread popularity of many composers (such as Joseph Egbert Turner, Henry George Nixon or John Richardson) within the English Catholic community have passed largely unnoticed. Worse still, much of the evidence is rapidly disappearing, partly because it no longer seems relevant to the needs of the modern Catholic Church in England.

This book provides a framework of the main aspects of Catholic church music in this period, showing how and why it developed in the way it did. Dr Muir sets the music in its historical, liturgical and legal context, pointing to the ways in which the music itself can be used as evidence to throw light on the changing character of English Catholicism. As a result the book will appeal not only to scholars and students working in the field, but also to church musicians, liturgists, historians, ecclesiastics and other interested Catholic and non-Catholic parties.

The article I cited from Newman's foundation, the Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England, points out that there were exceptions to the rule of secret and silent Masses, looking again at the Embassies in London and the outlet they offered to some Catholic composers, like Samuel Webbe, George Paxton--and Thomas Arne, arranger of "God Save the King/Queen" and composer of "Rule, Britannia". There is definitely more to this story.

Saturday, May 24, 2014

Limited Religious Tolerance in 1689

The Act of Toleration, after being passed in Parliament, was approved on May 24, 1689 by William and Mary (1 Will & Mary c 18). The long title of the Act reveals its limited scope: An Act for Exempting their Majesties Protestant Subjects dissenting from the Church of England from the Penalties of Certain Laws (modern spelling). It was limited to allowing some freedom of worship to some dissenters. Catholics and Unitarians were excluded from the Act of Toleration.

The Protestants who dissented from the Church of England (Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, etc.) were not "granted" freedom of religion and the Church of England remained the established church--its members had all the privileges of citizenship. England would certainly be protected from the dangers of Catholicism, as this paragraph emphasizes:

It's interesting to note that this Act of Toleration, and the "Ecclesiastical Enactments" of the Tudor English Reformation(s) were all repealed by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act of 1969. In fact, much of the legislation of the English Reformation was repealed by that Act: Henry VIII's, Edward VI's, and Elizabeth I's. For example, here are Henry's Acts undone:

Be it enacted by the King's and Queen's most excellent majesties, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and the Commons, in this present Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same, That neither the statute made in the three and twentieth year of the reign of the late Queen Elizabeth, intituled, An act to retain the Queen's majesty's subjects in their due obedience; nor the statute made in the twenty ninth year of the said Queen, intituled, An act for the more speedy and due execution of certain branches of the statute made in the three and twentieth year of the Queen's majesty's reign viz. the aforesaid act; nor that branch or clause of a statute made in the first year of the reign of the said Queen, intituled, An act for the uniformity of common prayer and service in the church, and administration of the sacraments; whereby all persons, having no lawful or reasonable excuse to be absent, are required to resort to their parish church or chapel, or some usual place where the common prayer shall be used, upon pain or punishment by the censures of the church, and also upon pain that every person so offending shall forfeit for every such offence twelve pence; nor the statute made in the third year of the reign of the late King James the First, intituled, An act for the better discovering and repressing popish recusants; nor that other statute made in the same year, intituled, An act to prevent and avoid dangers which may grow by popish recusants; nor any other law or statute of this realm made against papists or popish recusants, except the statute made in the five and twentieth year of King Charles the Second, intituled, An act for preventing dangers which may happen from popish recusants; and except also the statute made in the thirtieth year of the said King Charles the Second, intituled, An act for the more effectual preserving the King's person and government, by disabling papists from sitting in either house of parliament; shall be construed to extend to any person or persons dissenting from the Church of England, that shall take the oaths mentioned in a statute made this present Parliament, intituled, An act for removing and preventing all questions and disputes concerning the assembling and sitting of this present Parliament; and shall make and subscribe the declaration mentioned in a statute made in the thirtieth year of the reign of King Charles the Second, intituled, An act to prevent papists from sitting in either house of Parliament; which oaths and declaration the justices of peace at the general sessions of the peace, to be held for the county or place where such person shall live, are hereby required to tender and administer to such persons as shall offer themselves to take, make, and subscribe the same, and thereof to keep a register: and likewise none of the persons aforesaid shall give or pay, as any fee or reward, to any officer or officers belonging to the court aforesaid, above the sum of six pence, nor that more than once, for his of their entry of his taking the said oaths, and making and subscribing the said declaration; nor above the further sum of six pence for any certificate of the same, to be made out and signed by the officer or officers of the said court.Well, a Catholic take the oath required, but then he wouldn't really be a Catholic anymore, would he, because he'd have to deny the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist and the authority of the Pope!

It's interesting to note that this Act of Toleration, and the "Ecclesiastical Enactments" of the Tudor English Reformation(s) were all repealed by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act of 1969. In fact, much of the legislation of the English Reformation was repealed by that Act: Henry VIII's, Edward VI's, and Elizabeth I's. For example, here are Henry's Acts undone:

Friday, May 23, 2014

Newman, Eliot, and Brownson Comment on Girolamo Savonarola, OP

Girolamo Savonarola was executed in the main square of Florence on May 23, 1498--it was a brutal execution that came after the Dominican friar had been tortured. He and his companions were stripped of their habits (degradated) and hung by the neck above fires lit to burn their bodies. Their ashes were scattered in the Arno.

Savonarola was a hero to St. Philip Neri, as he had studied at the convent of San Marco (St. Mark's). Blessed John Henry Newman wrote about his patron's admiration of the Florentine friar in the two sermons he preached at the Oratory in Birmingham in 1848.

First, describing Savonarola:

A true son of St. Dominic, in energy, in severity of life, in contempt of merely secular learning, a forerunner of the Dominican St. Pius [V] in boldness, in resoluteness, in zeal for the honour of the House of God, and for the restoration of holy discipline, Savonarola felt "his spirit stirred up within him," like another Paul, when he came to that beautiful home of genius and philosophy; for he found Florence, like another Athens, "wholly given to idolatry." He groaned within him, and was troubled, and refused consolation, when he beheld a Christian court and people priding itself on its material greatness, its intellectual gifts, and its social refinement, while it abandoned itself to luxury, to feast and song and revel, to fine shows and splendid apparel, to an impure poetry, to a depraved and sensual character of art, to heathen speculations, and to forbidden, superstitious practices. His vehement spirit could not be restrained, and got the better of him, and—unlike the Apostle, whose prudence, gentleness, love of his kind, and human accomplishments are nowhere more happily shown than in his speech to the Athenians —he burst forth into a whirlwind of indignation and invective against all that he found in Florence, and condemned the whole established system, and all who took part of it, high and low, prince or prelate, ecclesiastic or layman, with a pitiless rigour,—which for the moment certainly did a great deal more than St. Paul was able to do at the Areopagus; for St. Paul made only one or two converts there, and departed, whereas Savonarola had great immediate success, frightened and abashed the offenders, rallied round him the better disposed, and elicited and developed whatever there was of piety, whether in the multitude or in the upper class.

It was the truth of his cause, the earnestness of his convictions, the singleness of his aims, the impartiality of his censures, the intrepidity of his menaces, which constituted the secret of his success. Yet a less worthy motive lent its aid; men crowded round a pulpit, from which others were attacked as well as themselves. The humbler offender was pleased to be told that crime was a leveller of ranks, and to find that he thus was a gainer in the common demoralization. The laity bore to be denounced, when the clergy were not spared; and the rich and noble suffered a declamation which did not stop short of the sacred Chair of St. Peter. . . .

A very wonderful man, you will allow, my Brethren, was this Savonarola. I shall say nothing more of him, except what was the issue of his reforms. For years, as I have said, he had his own way; at length, his innocence, sincerity, and zeal were the ruin of his humility. He presumed; he exalted himself against a power which none can assail without misfortune. He put himself in opposition to the Holy See, and, as some say, disobeyed its injunctions. Reform is not wrought out by disobedience; this was not the way to be the Apostle either of Florence or of Rome. Then trouble came upon him, a great reaction ensued; his enemies got the upper hand; he went into extravagances himself; the people deserted him; he was put to death, strangled, hung on a gibbet, and then burned in the very square where he had set fire to the costly furniture of vanity and sin.

And then of St. Philip Neri's connection to Savonarola:

Philip was born in Florence within twenty years after [Savonarola]. The memory of the heroic friar was then still fresh in the minds of men, who would be talking familiarly of him to the younger generation,—of the scenes which their own eyes had witnessed, and of the deeds of penance which they had done at his bidding. Especially vivid would the recollections of him be in the convent of St. Mark; for there was his cell, there the garden where he walked up and down in meditation, and refused to notice the great prince of the day; there would be his crucifix, his habit, his discipline, his books, and whatever had once been his. Now, it so happened, St. Philip was a child of this very convent; here he received his first religious instruction, and in after times he used to say, "Whatever there was of good in me, when I was young, I owed it to the Fathers of St. Mark's, in Florence." For Savonarola he retained a singular affection all through his life; he kept his picture in his room, and about the year 1560, when the question came before Popes Paul IV. and Pius IV., of the condemnation of Savonarola's teaching, he interceded fervently and successfully in his behalf before the Blessed Sacrament, exposed on the occasion in the Dominican church at Rome.

George Eliot--about as far in religious sympathy from Neri and Newman as you can be--placed Girolamo Savonarola's leadership and the great Bonfire of the Vanities at the center of her historical novel Romola. The title character is a follower of the great prophet and through the course of the novel (written for the Cornhill Magazine in fourteen parts) she witnesses his rise and fall. Please note that Eliot includes the story of Sandro Botticelli throwing some of his paintings based on classical mythology on the Bonfire. I read Romola--it is one of the least read of Eliot's works--several years ago and enjoyed the historical background more than the story of the heroine and her duplicitous husband!

Finally, one more Savonarola fan: the American Catholic convert Orestes Brownson (also rather lacking in sympathy with Blessed John Henry Newman!). Brownson addresses how Savonarola is often used to attack the Catholic hierarchy and the papacy, because he opposed Pope Alexander VI:

The name of Savonarola has become popular with the partisans of republican opinions and the adversaries of the Catholic hierarchy; and so often as that name is pronounced at the present day, it seems to recall exclusively the recollection of an ignominious death inflicted on one of the most energetic defenders of civil liberty and liberty of conscience. That which has, more than any thing else, contributed to this error, is the perseverance with which the eyes of posterity have been required to contemplate two facts, which are claimed to exhibit the sum and spirit of Savonarola's public life, namely, his having refused absolution to Lorenzo de' Medici at the point of death, unless he should first restore to his country its liberty, and the boldness with which he is said to have shaken off the authority of the Holy See. Without inquiring to what extent this twofold assertion is confirmed or disproved by the most authentic contemporary authorities, let us put ourselves at once at the point of view with which we are immediately concerned, and let us become spectators of that struggle at once so close, so dramatic, and so imposing which was maintained, in the presence of all Italy, by a simple monk against the spirit of his age. The object for which he strives is the restoration of the kingdom of Christ in the hearts, the intellect, and the imagination of the people, and to extend the advantages of the Redemption to all the faculties of man, and to all the works which they produce. The enemy which he combats is that Paganism, the mark of whose influence he finds impressed upon every thing,upon art as well as upon morals, upon opinions as well as upon conduct, upon the cloisters as well as upon the secular schools.

Read the rest here.

Savonarola was a hero to St. Philip Neri, as he had studied at the convent of San Marco (St. Mark's). Blessed John Henry Newman wrote about his patron's admiration of the Florentine friar in the two sermons he preached at the Oratory in Birmingham in 1848.

First, describing Savonarola:

A true son of St. Dominic, in energy, in severity of life, in contempt of merely secular learning, a forerunner of the Dominican St. Pius [V] in boldness, in resoluteness, in zeal for the honour of the House of God, and for the restoration of holy discipline, Savonarola felt "his spirit stirred up within him," like another Paul, when he came to that beautiful home of genius and philosophy; for he found Florence, like another Athens, "wholly given to idolatry." He groaned within him, and was troubled, and refused consolation, when he beheld a Christian court and people priding itself on its material greatness, its intellectual gifts, and its social refinement, while it abandoned itself to luxury, to feast and song and revel, to fine shows and splendid apparel, to an impure poetry, to a depraved and sensual character of art, to heathen speculations, and to forbidden, superstitious practices. His vehement spirit could not be restrained, and got the better of him, and—unlike the Apostle, whose prudence, gentleness, love of his kind, and human accomplishments are nowhere more happily shown than in his speech to the Athenians —he burst forth into a whirlwind of indignation and invective against all that he found in Florence, and condemned the whole established system, and all who took part of it, high and low, prince or prelate, ecclesiastic or layman, with a pitiless rigour,—which for the moment certainly did a great deal more than St. Paul was able to do at the Areopagus; for St. Paul made only one or two converts there, and departed, whereas Savonarola had great immediate success, frightened and abashed the offenders, rallied round him the better disposed, and elicited and developed whatever there was of piety, whether in the multitude or in the upper class.

It was the truth of his cause, the earnestness of his convictions, the singleness of his aims, the impartiality of his censures, the intrepidity of his menaces, which constituted the secret of his success. Yet a less worthy motive lent its aid; men crowded round a pulpit, from which others were attacked as well as themselves. The humbler offender was pleased to be told that crime was a leveller of ranks, and to find that he thus was a gainer in the common demoralization. The laity bore to be denounced, when the clergy were not spared; and the rich and noble suffered a declamation which did not stop short of the sacred Chair of St. Peter. . . .

A very wonderful man, you will allow, my Brethren, was this Savonarola. I shall say nothing more of him, except what was the issue of his reforms. For years, as I have said, he had his own way; at length, his innocence, sincerity, and zeal were the ruin of his humility. He presumed; he exalted himself against a power which none can assail without misfortune. He put himself in opposition to the Holy See, and, as some say, disobeyed its injunctions. Reform is not wrought out by disobedience; this was not the way to be the Apostle either of Florence or of Rome. Then trouble came upon him, a great reaction ensued; his enemies got the upper hand; he went into extravagances himself; the people deserted him; he was put to death, strangled, hung on a gibbet, and then burned in the very square where he had set fire to the costly furniture of vanity and sin.

And then of St. Philip Neri's connection to Savonarola:

Philip was born in Florence within twenty years after [Savonarola]. The memory of the heroic friar was then still fresh in the minds of men, who would be talking familiarly of him to the younger generation,—of the scenes which their own eyes had witnessed, and of the deeds of penance which they had done at his bidding. Especially vivid would the recollections of him be in the convent of St. Mark; for there was his cell, there the garden where he walked up and down in meditation, and refused to notice the great prince of the day; there would be his crucifix, his habit, his discipline, his books, and whatever had once been his. Now, it so happened, St. Philip was a child of this very convent; here he received his first religious instruction, and in after times he used to say, "Whatever there was of good in me, when I was young, I owed it to the Fathers of St. Mark's, in Florence." For Savonarola he retained a singular affection all through his life; he kept his picture in his room, and about the year 1560, when the question came before Popes Paul IV. and Pius IV., of the condemnation of Savonarola's teaching, he interceded fervently and successfully in his behalf before the Blessed Sacrament, exposed on the occasion in the Dominican church at Rome.

George Eliot--about as far in religious sympathy from Neri and Newman as you can be--placed Girolamo Savonarola's leadership and the great Bonfire of the Vanities at the center of her historical novel Romola. The title character is a follower of the great prophet and through the course of the novel (written for the Cornhill Magazine in fourteen parts) she witnesses his rise and fall. Please note that Eliot includes the story of Sandro Botticelli throwing some of his paintings based on classical mythology on the Bonfire. I read Romola--it is one of the least read of Eliot's works--several years ago and enjoyed the historical background more than the story of the heroine and her duplicitous husband!

Finally, one more Savonarola fan: the American Catholic convert Orestes Brownson (also rather lacking in sympathy with Blessed John Henry Newman!). Brownson addresses how Savonarola is often used to attack the Catholic hierarchy and the papacy, because he opposed Pope Alexander VI:

The name of Savonarola has become popular with the partisans of republican opinions and the adversaries of the Catholic hierarchy; and so often as that name is pronounced at the present day, it seems to recall exclusively the recollection of an ignominious death inflicted on one of the most energetic defenders of civil liberty and liberty of conscience. That which has, more than any thing else, contributed to this error, is the perseverance with which the eyes of posterity have been required to contemplate two facts, which are claimed to exhibit the sum and spirit of Savonarola's public life, namely, his having refused absolution to Lorenzo de' Medici at the point of death, unless he should first restore to his country its liberty, and the boldness with which he is said to have shaken off the authority of the Holy See. Without inquiring to what extent this twofold assertion is confirmed or disproved by the most authentic contemporary authorities, let us put ourselves at once at the point of view with which we are immediately concerned, and let us become spectators of that struggle at once so close, so dramatic, and so imposing which was maintained, in the presence of all Italy, by a simple monk against the spirit of his age. The object for which he strives is the restoration of the kingdom of Christ in the hearts, the intellect, and the imagination of the people, and to extend the advantages of the Redemption to all the faculties of man, and to all the works which they produce. The enemy which he combats is that Paganism, the mark of whose influence he finds impressed upon every thing,upon art as well as upon morals, upon opinions as well as upon conduct, upon the cloisters as well as upon the secular schools.

Read the rest here.

Thursday, May 22, 2014

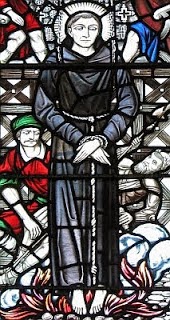

Blessed John Forest, Unique Among the Catholic Martyrs

Blessed John Forest is unique among the Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation. He is what I would call a Supremacy Martyr, suffering for his refusal to recognize Henry VIII's supremacy over the Church of England, but he was found guilty, not of treason but of heresy--and thus burned alive in chains by the order of Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

As one of the Observant Franciscans and as one of Queen Katherine of Aragon's chaplains and confessors, Blessed John Forest (beatified by Pope Leo XIII), was always opposed to what Henry VIII planned to do to resolve his "Great Matter", manipulating the Catholic Faith in England and attempting to do so in Rome to achieve his goal of marrying Anne Boleyn. The Thomas Abel mentioned below was another one of Katherine of Aragon's chaplains, executed along with two others (and three Zwinglians) two years later. Father Peto's sermon at Greenwich compared Henry VIII to Ahab and Anne Boleyn to Jezebel and occasioned threats from Thomas Cromwell that Peto and his defender Friar Elstow mocked as ineffective to those who did not fear death. Blessed John Forest endured imprisonment and a torturous death to defend the sanctity of marriage and unity of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

From the Catholic Encyclopedia, details about the blessed martyr's life and death:

Born in 1471, presumably at Oxford, where his surname was then not unknown; suffered 22 May, 1538. At the age of twenty he received the habit of St. Francis at Greenwich, in the church of the Friars Minor of the Regular Observance, called for brevity's sake "Observants". Nine years later we find him at Oxford, studying theology. He is commonly styled "Doctor" though, beyond the steps which he took to qualify as bachelor of divinity, no positive proof of his further progress has been found. Afterwards he became one of Queen Catherine's chaplains, and was appointed her confessor. In 1525 he appears to have been provincial, which seems certain from the fact that he threatened with excommunication the brethren who opposed Cardinal Wolsey's legatine powers. Already in 1531 the Observants had incurred the king's displeasure by their determined opposition to the divorce; and no wonder that Father Forest was soon singled out as an object of wrath. In November, 1532, we find the holy man discoursing at Paul's Cross on the decay of the realm and pulling down of churches. At the beginning of February, 1533 an attempt at reconciliation was made between him and Henry: but a couple of months later he left the neighbourhood of London, where he was no longer safe. He was probably already in Newgate prison 1534, when Father Peto [gave] his famous sermon before the king at Greenwich. In his confinement Father Forest corresponded with the queen and Blessed Thomas Abel and wrote a book or treatise against Henry, which began with the text: "Neither doth any man take the honour to himself, but he that is called by God as Aaron was.

On 8 April, 1538, the holy friar was taken to Lambeth, where, before Cranmer, he was required to make an act of abjuration. This, however, he firmly refused to do; and it was then decided that the sentence of death should be carried out. On 22 May following he was taken to Smithfield to be burned. The statue of "Darvell Gatheren" which had been brought from the church of Llanderfel in Wales, was thrown on the pile of firewood; and thus, according to popular belief, was fulfilled an old prophecy, that this holy image would set a forest on fire. The holy man's martyrdom lasted two hours, at the end of which the executioners threw him, together with the gibbet on which he hung, into the fire. Father Forest, together with fifty-three other English martyrs, was declared Blessed by Pope Leo XIII, on 9 December, 1886, and his feast is kept by the Friars Minor on 22 May.

“Most Serene Lady and Queen, my daughter most dear in the bowels of Christ, - When I read your letter I was filled with incredible joy, because I saw how great is your constancy in the Faith.

In this, if you persevere, without doubt you will attain salvation.

Doubt not of me that by any inconstancy I should disgrace my grey hairs.

Meanwhile I earnestly beg your steadfast prayers to God, for whose spouse we suffer torments, to receive me into His glory.

For it have I striven these four and forty years in the Order of St Francis.

Meanwhile do you keep free from the pestilent doctrine of the heretics, so that even if an angel should come down from Heaven and bring you another doctrine from that which I have taught you, give no credit to his words, but reject him; for that other doctrine does not come from God.

These few words you must take in lieu of consolation; but that you will receive from our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom I specially commend you, to my father Francis, to St Catherine; and when you hear of my execution, I heartily beg of you to pray for me to her.

I send you my rosary as I have but three days to live.”

As one of the Observant Franciscans and as one of Queen Katherine of Aragon's chaplains and confessors, Blessed John Forest (beatified by Pope Leo XIII), was always opposed to what Henry VIII planned to do to resolve his "Great Matter", manipulating the Catholic Faith in England and attempting to do so in Rome to achieve his goal of marrying Anne Boleyn. The Thomas Abel mentioned below was another one of Katherine of Aragon's chaplains, executed along with two others (and three Zwinglians) two years later. Father Peto's sermon at Greenwich compared Henry VIII to Ahab and Anne Boleyn to Jezebel and occasioned threats from Thomas Cromwell that Peto and his defender Friar Elstow mocked as ineffective to those who did not fear death. Blessed John Forest endured imprisonment and a torturous death to defend the sanctity of marriage and unity of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.

From the Catholic Encyclopedia, details about the blessed martyr's life and death:

Born in 1471, presumably at Oxford, where his surname was then not unknown; suffered 22 May, 1538. At the age of twenty he received the habit of St. Francis at Greenwich, in the church of the Friars Minor of the Regular Observance, called for brevity's sake "Observants". Nine years later we find him at Oxford, studying theology. He is commonly styled "Doctor" though, beyond the steps which he took to qualify as bachelor of divinity, no positive proof of his further progress has been found. Afterwards he became one of Queen Catherine's chaplains, and was appointed her confessor. In 1525 he appears to have been provincial, which seems certain from the fact that he threatened with excommunication the brethren who opposed Cardinal Wolsey's legatine powers. Already in 1531 the Observants had incurred the king's displeasure by their determined opposition to the divorce; and no wonder that Father Forest was soon singled out as an object of wrath. In November, 1532, we find the holy man discoursing at Paul's Cross on the decay of the realm and pulling down of churches. At the beginning of February, 1533 an attempt at reconciliation was made between him and Henry: but a couple of months later he left the neighbourhood of London, where he was no longer safe. He was probably already in Newgate prison 1534, when Father Peto [gave] his famous sermon before the king at Greenwich. In his confinement Father Forest corresponded with the queen and Blessed Thomas Abel and wrote a book or treatise against Henry, which began with the text: "Neither doth any man take the honour to himself, but he that is called by God as Aaron was.

On 8 April, 1538, the holy friar was taken to Lambeth, where, before Cranmer, he was required to make an act of abjuration. This, however, he firmly refused to do; and it was then decided that the sentence of death should be carried out. On 22 May following he was taken to Smithfield to be burned. The statue of "Darvell Gatheren" which had been brought from the church of Llanderfel in Wales, was thrown on the pile of firewood; and thus, according to popular belief, was fulfilled an old prophecy, that this holy image would set a forest on fire. The holy man's martyrdom lasted two hours, at the end of which the executioners threw him, together with the gibbet on which he hung, into the fire. Father Forest, together with fifty-three other English martyrs, was declared Blessed by Pope Leo XIII, on 9 December, 1886, and his feast is kept by the Friars Minor on 22 May.

The Guild of Blessed Titus Brandsma blog posted this information about the friar's correspondence with Katherine of Aragon:

In this, if you persevere, without doubt you will attain salvation.

Doubt not of me that by any inconstancy I should disgrace my grey hairs.