I have been mulling over this review essay by Felipe Fernandez-Arnesto from the Wall Street Journal a couple of weeks ago. The author of the essay is a fine historian and academic and he is actually rather gentle in his dismantling of four amateur historians' books about Columbus and the Age of Exploration. But he wrote some things I've been wondering about:

History is the people's discipline—the only academic subject that demands no special professional training. Some of my favorite history books are by lawyers, journalists, scientists and nuns. To write well about history you do not need a Ph.D., just a few rare but accessible qualities: insatiable curiosity, critical intellect, disciplined imagination, indefatigability in the pursuit of truth and a slightly weird vocation for trying to get to know dead people by studying the sources they have left us. To write well about anything, of course, you also have to follow the advice that every writing course gives: Write about what you know. . . .

I have studied and continue to study the history of the English Reformation, so I am writing about what I know. I think that I do have the qualities Fernandez-Arnesto mentions: curiosity, critical thinking skills, imagination, pursuit of truth, and weirdness. So I didn't think I was too much in trouble there. But later in the article, after he has pointed out many of the four authors' errors, he focused on some of the causes of their trouble: deficiencies in using primary sources and particularly, the lack of linguistic ability.

To some extent, scholars may have encouraged these amateurs' imprudence by publishing English translations of many of the sources. Translated sources attract errors just as translated scriptures foment heresies, and when the inexperienced attempt their own translations, the results can be even worse. Mr. Bergreen, Mr. Cliff, Mr. Hunter and Ms. Delaney do not have the linguistic skills to master the literature on their own. They all seem to be illiterate in Latin and imperfectly assured in handling the sources in Romance languages. In Mr. Hunter's case the deficiency is fatal, as his grounds for linking Cabot and Columbus rest largely on a glaring mistranslation, which warps a difficult but perfectly intelligible and well-known document, in which a Spanish ambassador in England compared the two explorers. Mr. Hunter mistakes a neuter pronoun for a masculine one, making the ambassador call Cabot the man "from the Indies," whereas the text really refers to "the business of the Indies." . . .

Now my Latin is rusty, except for liturgical Latin which has been revived by our attendance at Masses in the Extraordinary Form almost every Sunday. Once when I was in graduate school, a great professor taught a class on Dostoevsky. We read all his great works and some of his diary and short stories. He almost did not teach the course because he could not read the originals in Russian! He could read the French translations, however, and told me that all that would be required for doctorate level study of Dostoevsky would be French and German--one could get by and be able to keep up on the scholarship with those two languages. By now, my facility with French is weaker, although I can understand it when I read it--but I cannot translate it--and I have never studied German. So I would fail the author's test and could find myself in trouble.

Academic historians tend to welcome recruits from other ranks, like owls nurturing cuckoos, and applaud the intrusions of neophytes with a glee that physicians, say, would never show for faith-healers or snake-oil salesmen. I am afraid it is time for historians to wipe the smiles from our jaws and start biting back. If escape from the poverty of your own imagination is your reason for exploiting the stories history offers, or if you are taking refuge from another discipline in the belief that history is easy, without bothering to do the basic work, you will deserve to fail.

I certainly don't think that history is easy--I think it is hard to write about the past because I have to balance the details of the facts with their relevance and interpretation. And all the while, I try to make it interesting and let the story shine through so it's not boring. At the same, I don't want to sensationalize or over-interpret. "Indolent cupidity"--if I desired wealth from writing, I certainly have failed.

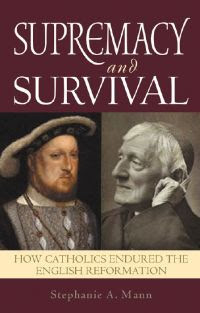

"Parade their inadequacies": that phrase is scary to any writer who chooses to publish on a blog, in a magazine, or a book on the shelf (and in the e-reader device). It takes a mixture of chutzpah and humility to write and publish. Fortunately for me, I found myself standing on the shoulders of giants like Eamon Duffy, Blessed John Henry Newman, Father John Lingard and even Alister McGrath, who helped me confirm my interpretation of the English Reformation. When I read his book on the Protestant Reformation, Christianity's Dangerous Idea, I was exceptionally pleased to see that he confirmed my views about Henry VIII's political reformation, the legislative compromise of the Elizabethan religiouis settlement, and even some of my thoughts on the continuing Stuart and Puritan manipulation of religion in the established church. I don't think that I have written drivel.

|

| Brandy as a puppy |

Professor Fernandez-Arnesto is particularly correct about the television history which irritates me so much that my little dog Brandy gets scared when I react to a show on the historical Jesus or the Crusades, or anything on Church History. The way the programs are structured to avoid getting to the truth, or even, once the truth has been revealed, casting doubt upon the truth--it upsets me so! Brandy thinks I'm mad at her, so I quickly change the channel, calm down, and tell her she's a good dog. She is really, when she isn't stealing socks.

Please let me know what you think about reading or writing popular history, dear readers.

You would think being stared down by that frightful beast above would be enough to keep everyone orthodox in their historical interpretations.......

ReplyDeleteI think you are doing a great job. He is talking about people who churn out sensational junk.

ReplyDeleteLord Have Mercy.

ReplyDeleteYou are only too objective, Madame. And may you stay that way.

My late PitBull, Emily Louise, could also sense my anger with the so-called "History Chanel"; She would whine until I turned off the TV and played upbeat Italian Baroque music on the stereo.

Dear Elena Maria and tubbs, thank you very much. tubbs, we call the "History Channel" the "Fantasy Channel"!

ReplyDeleteHon, I think you have nothing to worry about! If the professor is using harsh invectives, it's likely for the same reasons you have to turn off the TV. Coming from the southeastern corner of the United States and now living in Poland, dealing with the abuse of history is enough to make one apoplectic!

ReplyDelete'The Church exploited the Indians...'

'Martin Luther was never a priest!'

'The Polish calvary was stupid enough to charge German tanks...'

'Poland has a long tradition of being anti-Semitic...'

Blah, blah, blah! On the list of lies go.

And when you find out where these silly people got those ideas, it's hard not to sound condescending when pointing out that they should read history, not pop history. Bad history leads souls astray and turns minds upside down. Fernandez-Arnesto may single out such things as poor mastery of a language, but the truth is that it's a bad will that creates a bad record.

Thanks Jacobitess--you are right that there's a kind of ill will or willfull element of some interpretations that is behind some of the popular history.

ReplyDeleteI'm posting as "anonymous" because I don't know how to do otherwise. I'm Ruth Lasseter and can be contacted at rdlasseter@yahoo.com. Thanks for your blog! Please take the following comment as a plea for history's restoration to its rightful place in the education of our children and not as a plug from a sales-opportunist. Take a look at the Catholic Schools Textbook Project at this website: www.CatholicTextbookProject.com My late husband, Rollin A. Lasseter, was the general editor and author of two of these books; his colleague, Christopher Zehnder, has taken up the task which my husband was obliged to leave unfinished. These textbooks are historically accurate, beautiful, well-made, interesting and the Catholic Faith infuses the whole series of 4 books (5th-high school) without becoming oppressive. There is a write up in the Official Catholic Directory 2011 on page 5 on the C.S.T.P. Those who have written and produced these books have done so at great financial sacrifice, and there is no money for advertising -- book sales, spread entirely by word of mouth, keep our project going. Thanks.

ReplyDelete